“When you reach that elite level, 90 percent is mental and 10 percent is physical. You are competing against yourself. Not against the other athlete.” - Dick Fosbury

Dick Fosbury, tall, with an athletic frame, discovered his love of high jumping in high school. Yet, despite a seemingly ideal physique, he struggled immensely - ultimately failing to clear the qualifying jumps at many of his track meets.

At the time, in the late 1960s, the straddle method was seen as the pinnacle approach to clearing the high jump bar.

Run straight.

Slight turn.

Jump face down.

Lift each leg over, one by one.

But the coordination to pull it off was too much for Fosbury. A dilemma. He knew even if he trained adequately using the approach to qualify, he’d never excel enough to win.

Fosbury attempted the upright scissors method; to no avail. Undeterred, he began to change his approach. Slowly but surely, his movements became bizarre - unrecognizable - compared to the popular methods of the day. Ultimately, his technique involved jumping over the bar backward, arching his body head-first, and kicking his legs upwards once partly over. His coaches, apprehensive, would have talked him out of continuing if not for the fact his performance was starting to impress them.

Fosbury’s determination led him to breaking his high school’s record, provided a successful college career at Oregon State University, and allowed him to win the U.S. Olympic Trials in August of 1968. His technique, fully refined and which had previously been referred to as “looking like a fish flopping in a boat”, earned him the gold medal at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

Changing the world of high jump forever, the technique would forever be coined:

The Fosbury Flop.

The physics of the technique are unmatched, allowing athletes to perfectly shift their velocity and bend over the bar while maintaining their center of mass underneath. If you’ve watched any track events over recent decades, the Fosbury Flop is nothing out of the ordinary. Nearly every athlete has adopted the approach. But the origin story imparts a key truth:

Innovation is always first ridiculed.

Clearing the highest bar

Even with his recent forays into hydrofoiling and MMA, Mark Zuckerberg is probably the last person you’d think of when discussing elite athletes. However, he’s elite in his own right and over the last decade has expertly navigated the shift from desktop to mobile, made several brilliant acquisitions, and has seen the user base of his core platform balloon from millions to billions. Revenue from FY 2012 to the current trailing twelve months has grown from $5.089 billion to a staggering $118.115 billion, which is arguably worthy of a gold medal. And not unlike Fosbury, Zuckerberg is no stranger to criticism. Presently, he stands accused of flopping, flailing, and failing, which I covered in Meta: Pain and Patience. In that piece, I wrote:

There may be seemingly exponential rewards to be had, but what if the competition can’t afford the costs? Most are already two (or more) steps behind, are nowhere near as profitable, and simply will never have deployable capital to match what Meta has built, let alone what it is building. Now, with rates increasing, the hurdle continues to grow taller, and just as in 2018, I expect it to be further increased by privacy-oriented regulations over time.

Again, like Fosbury, Zuckerberg’s moves are seen as bizarre by most, but all aim to achieve one single goal:

Clearing the highest bar.

The goal of any advertising platform is to offer advertisers a clear return on capital over their cost of capital. This is true of all cost models, including CPC, CPM, CPL, CPA, etc., and is true for both brand and DR advertising. If you can do that, you clear the ‘qualifying bar’.

But it isn’t always straightforward.

Bidding models, such as in Meta’s case, cause advertising costs to fluctuate from a wide variety of factors. Since returns are largely a function of price paid, specific campaigns can shift from viable to unviable and vice versa. Sometimes quickly. Nearly always contingent on market appetite. Additionally, determining the value of certain forms of brand advertising, which may be longer-term oriented and carry certain qualitative properties, can prove to be difficult relative to DR (direct response) advertising, which aims to generate near-immediate conversions and may be measured strictly through a financial lens in a prompt fashion.

Firmly breaching the qualifying bar also requires platforms to provide advertisers with access to robust tools to assist in deploying and managing spend, efficient targeting, and attribution. Ideally, measurable success can also be replicated and even scaled. Historically, Meta has led in all of these regards. But the recent confluence of Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT), which degraded targeting and attribution capabilities, Meta’s push to Reels, which currently monetizes at lower rates to incumbent media, and macro factors, which have curbed advertisers’ total appetite, has allowed people to forget something: Meta is still leading.

Even accounting for the fact that ATT effectively killed a portion of the digital economy, Meta, relative to other social platforms, offers the most easily accessible suite of tools for advertisers to generate meaningful returns. Meta had cleared the qualifying bar by such a huge degree that it’s still in first place. Even more important is the fact that the bar is never getting lowered. In fact, it’s only going to continue to get higher.

And that is a very good thing for Meta.

The impossible hurdle

~18% of Meta’s total spending is going towards Reality Labs’ Metaverse. A good chunk of that is going toward VR headsets and as Zuckerberg framed in his recent DealBook Summit interview, perhaps it isn’t the craziest pursuit:

You know we're selling quite a few units. I think we're investing a level that is sort of on par with what Microsoft did when investing in Xbox at its peak. So I think the results that we're seeing right now are kind of like a game console. So, obviously, we don't aspire to just build a game console, you know, we want it to be a general computing platform. But I think it's pretty likely that you know a downside case is that's where it turns out and I don't think Microsoft regrets building the Xbox. So I think that’s fine.

While some claim the Metaverse pursuit is some crazed fantasy Zuckerberg is chasing, I think a more likely explanation is that he wants to free his platforms from the iron rule of Apple’s hardware. Regardless, I am not convinced it will result in much of anything. What I am much more interested in is the remaining ~82% of spend, which is going towards the core business, Family of Apps (FOA). As I highlighted previously, it’s primarily going into three buckets:

Probabilistic modeling for ad targeting and attribution.

Requisite compute to support short-form video (Reels).

Switching from a social graph to an open graph, expanding served content from a much deeper pool.

Unlike Reality Labs, the investments in these areas are already showing results. There are more people using FoA on a daily and monthly basis than ever before and Reels have become incremental to time spent on platform, despite the fact that the company is not optimizing for time spent (if they were, they’d prioritize longer-form video). Meta CFO Susan Li reiterated the rationale for these investments on the Q3 2022 call:

We're very focused on evaluating the ROI of our AI investments, and that'll inform our level of future spend. But so far, we've seen continued strong impact on our recommendations products from advancing developments and in our AI work.

In the Q2 call, we had shared that a single AI advancement in scaling our recommendations models had led to a 15% watch time gain for Facebook Reels, and that gain has continued to grow. And we expect that there will be additional watch time improvements coming from that work.

On the ad side, we're also continuing to roll out more AI and ML improvements in some of the new ads offerings, and we're encouraged by all of the early examples that we've seen. So this is something that we'll be watching very closely.

We think we're early in this journey, but our level of CapEx investment will depend on the returns that we generate through these investments in AI. And if we generate significant engagement and revenue gains, we'll continue investing here. And if we don't, we'll pace our spending accordingly.

This may all sound positive, but there is one distinct drawback:

All of this is insanely expensive.

2023 CapEx is expected to be in the $34-39 billion range. R&D will likely be in the same area. These kinds of numbers seem absolutely nuts, especially when compared to previous years. But, as provable results have already been generated, it’s very conceivable that Meta’s core investments continue to pay off. Even if you want to assume that DAP/MAP/DAU/MAU remain flat, the value equation can incrementally compound: more time spent on platform x better targeting and attribution x improved ad density (load) = growing revenue. This can produce very robust results if global advertising spending continues to grow LSD and the shift to digital grows at MSD. Critically, the scale of these investments can not be matched by any other existing platform.

But the greatest returns may come from the unexpected angle of privacy.

Privacy-oriented regulations are often cited to be the bane of Meta. However, relative to other platforms, Meta will produce magnitudes more high-quality first-party data, and probabilistic modeling will allow incremental improvements while using limited sensitive data. While the company will certainly be impacted by new regulations, sometimes severely, it is almost assuredly best positioned each and every time. Even in worst-case scenarios, Meta will contest and appeal ad nauseam, which delays each threat for potentially years. Add on several more years until Meta is forced to choose between caving to said policies or continuing business as usual and assessing the forecasted fines as a cost of doing business - something which only those with deep pockets can afford. Naturally, the fines themselves will also be challenged, drawn out, and perhaps settled down and only paid many years later. Either way, most current competition simply can’t afford to navigate the space in the same capacity, and new competition is disincentivized from entering. To many people’s disappointment, rather than killing Meta, these pressures are more likely to ultimately insulate the company and protect its supernormal profitability. Every inch the bar is raised translates to substantial incremental returns for Meta and competitors losing share.

Extreme capital requirements.

Massive economies of scale.

Complex government policies.

Advanced intellectual property.

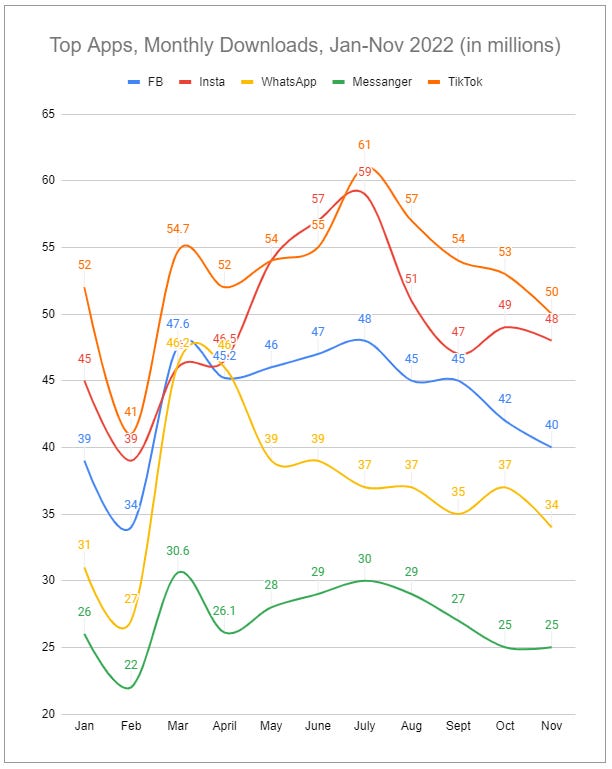

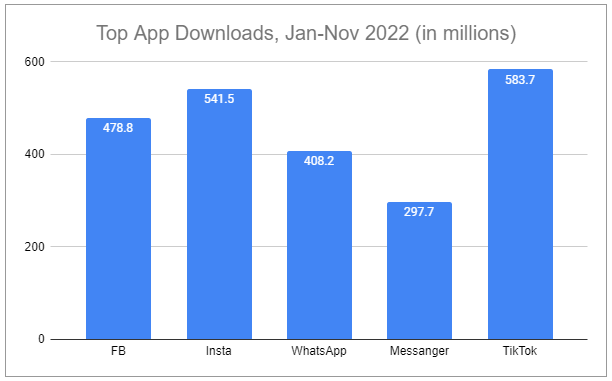

There is no other social platform truly competing with Meta in terms of investment. Even for TikTok, engagement may be starting to stagnate and monthly downloads continue to show TikTok falling toward parity with Instagram while the rest of FoA continues marching forward:

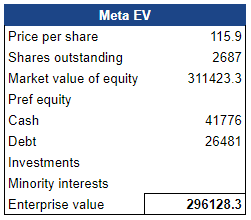

Valuation

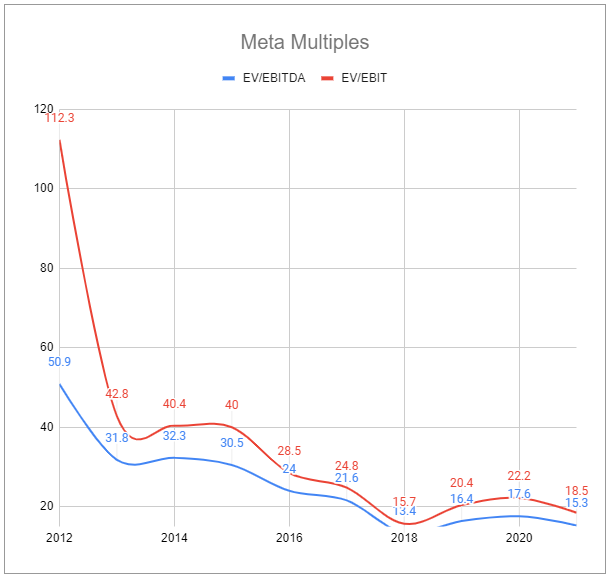

It’s rather interesting to see how Meta’s multiples have come down as it’s grown into itself:

While people often cite the abysmally low EV/EBITDA multiple, that probably doesn’t make too much sense for a company that is in the middle of an aggressive investment cycle and whose D&A will surely continue to grow significantly.

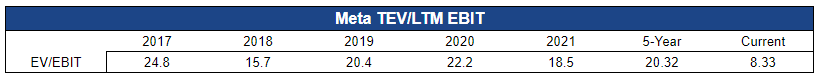

Even looking at the trailing twelve-month EV/EBIT multiple shows something similar.

However, total expenses for 2022 are guided to be between $85-87 billion and are guided to grow to between $96-101 billion for FY 2023. While still facing near-term headwinds, 2023 EV/EBIT could rest in the x10-13 range. Even so, that doesn’t sound half bad for potential bottom-of-the-trough earnings for the most dominant player in a lucrative and growing market.

TTM EBITDA = $43.867 billion

TTM EBIT = $35.543 billion

But what’s most interesting to me is that a great deal of concern and criticism around Meta’s spend is unwarranted. People act as if Zuckerberg is a disastrous capital allocator. Historically, he is not.

The immense spending associated with FoA will come down post the end of the growth investment cycle in 2023. Over the medium term, I believe the most reasonable expectations include a sizable reduction in CapEx and a slowing in R&D. Remaining spending is more likely than not to yield incremental results. If not, it too will be cut. Even with modest single-digit topline growth (which could be driven higher), this could result in a 2024 EBIT well north of $40 billion. This would be even with RL/Metaverse spending continuing to burn a hole in Meta’s pocket. Just as incremental FoA spending will be cut if not yielding results, I would expect the same for RL/Metaverse, though it may take many more years to see that happen.

In this scenario, there’s no need for the market to wake up or warm up to this company. Ultimately, what we’d end up with is an abnormally profitable market leader with zero net debt, still set to grow, at an EV/EBIT multiple between x5.5-7.5. Even accounting for concerns like ballooning SBC, an increasing effective tax rate, and ongoing regulatory pressures, the company would be presenting a robust double-digital shareholder yield.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment here or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

At the time of this publishing, I own positions in Meta.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Tags: META 5.26%↑ GOOG 2.04%↑ PINS -0.08%↓ SNAP -0.47%↓ TTD 8.74%↑

Are we we are letting Zuck off the hook saying "on par with what Microsoft did when investing in Xbox at its peak"? Xbox was just copying/offering a slight alternative to a existing multi-decade profit proven console platform so less risky than creating a new category? It is nice to see he is going to focus on FoA as he has great birds in the hand already.

Great writing!