“I’m hungrier than those other guys out there. Every rebound is a personal challenge.” - Dennis Rodman

In April 2016, Christopher Cole, Founder and CIO of Artemis Capital Management, published a thought-provoking paper exploring volatility as an asset class and its role in portfolio optimization. The core of the argument boiled down to the convex nature of long volatility exposure, which can produce substantial non-linear returns during major linear declines in equity markets. This allows one to buy assets when they are far below intrinsic value and certainly helps one maintain portfolio discipline during the most rocky periods. For those of us without a deep understanding of advanced volatility modeling and its implications, the paper offers an approachable and digestible framework using a much more easily understood sports metaphor. The paper, Dennis Rodman and the Art of Portfolio Optimization, is uniquely valuable and deserves to be read in its entirety (If you find yourself reading this at a later date and the link no longer works, email me, and I will send you a PDF version.)

The most instinctive response to Cole’s premise is a counter question: Isn’t that what bonds are for? However, Cole directly addresses such notions by pointing out the fact that, over a much longer history, bonds and stocks have not held an inverse correlation. In fact, more often than not, they have been positively correlated, with multi-year periods in which both have declined. Preconceived notions that bonds will miraculously save portfolios when (never if) things turn brutishly ugly must be checked. But those checks are not occurring, Cole argues, because many professionals, namely institutions, have continued to rely on bonds simply because of their positive carry. And so, the truly thought-provoking aspect of the paper, to me, is not necessarily the role of long volatility but rather the anomalous notion that positive returns can be enhanced by certain assets that, in isolation, have limited positive scoring potential. In other words, the best offense is a good defense. This is what Dennis Rodman perfectly illustrates (emphasis added):

Rodman was better at rebounding relative to his peers than any other player at any other skill, including points and assists. At 6’7’’ in an era of powerhouse 7’+ centers, he garnered a remarkable and statistically unmatched 30% of the defensive rebounds, and 17% of offensive rebounds, while simultaneously guarding anyone from Magic Johnson to Shaq. He led the league in rebounding a record seven consecutive years. At his peak, he was over six standard deviations better at rebounding than anyone else in the league. In one game Rodman single handedly outrebounded the opposing team. No other player has ever achieved this degree of statistical separation in any other skill, even his three-time teammate, Michael Jordan.

Rodman dominated the game without scoring by dramatically improving the statistical efficiency of his teammates via rebounding and defense. His rebounding prowess on both ends of the floor resulted in countless second chance scoring opportunities and higher per possession utility. How many Michael Jordan jump shots, Isaiah Thomas layups, or David Robinson dunks began from a Rodman rebound? Rodman had a measurable impact on the per-possession efficiency of his team when played. Counter-intuitively, his team’s shooting percentages improved dramatically when Rodman was on the floor despite the fact that he was a terrible shooter himself and rarely needed to be guarded!

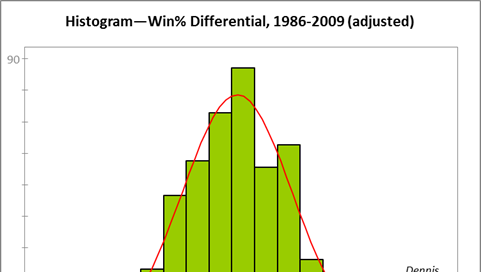

Numerous onlookers have performed significant statistical analyses to dissect the careers of professional athletes. Where Rodman is concerned, no documentation is as complete or more compelling than that of Ben Morris’s series, The Case for Dennis Rodman, on Skeptical Sports Analysis, which Cole cited in his paper. Along with several of the same figures cited, I believe additional charts best capture Rodman’s outlier status:

It is easy to criticize the idea that Rodman’s career can still be compared to the NBA of today. Rules have changed; the league has lost the close-combat-like physicality of decades prior; roles on the court have become more fluid; positioning has gravitated away from the hoop and outward past the three-point line. But despite the league appearing more offensively-oriented, defense can not be simply ignored, and in markets, ignoring defensive capabilities proves even more problematic.

In basketball, scoring is purely an additive system of ones, twos, and threes. Each game begins from a base of zero, and the scoring of one game does not carry over directly to the next. In investing, however, scoring is a radically different function. Your score, currently, is far above zero, represented by the capital you have invested. There is no cap on the points a single shot can score, and rather than being additive, baskets have a multiplicative effect. That is certainly an alluring proposition; however, the stakes are also high. Baskets scored on the other end of the court do not just add to a separate score but rather detract from your own. Even worse, the amount is not subtracted as a flat amount but is instead a percentage. The stakes are raised even further. There are cycles but no seasons. It is one game, played without end. This should force serious reflection toward equity strategies strictly focused on a few potentially high-scoring shots. Sure, in your wildest dreams, you can hit five, ten, or twenty in a row. But if a single crazy full-court throwaway can go nothing-but-net into the other hoop, it really doesn’t matter how perfectly your time team played prior. Drafting new players can’t happen if you can’t pay them. With broad equities at lofty multiples and so many segments of the market appearing stretched, having those who can guard, block, and rebound is a must. Protecting your score, capital, is paramount.

Can other equities offer that protection while also enhancing future scoring opportunities? Such a question may seemingly suggest the tired outcries of growth vs. value, but the classic growth vs. value argument is, at its core, a bit of a misnomer. These are two sides of the same coin. All sensible investing is about value: Putting in dollars to get more dollars out in the future at an adequate rate, accounting for risks and the pesky, unavoidable passage of time. Growth is a function of the reinvestment rate and the incremental returns that incremental investments can produce. At its core, the issue is really more of a matter of duration.

Companies that fall into the classification of ‘growth companies’ are presumed to have ample reinvestment opportunities, the capital to meet the requirements of those opportunities, and future opportunities will remain ample for many years. Those classified as strictly ‘value companies’ are mature, having run that course, and now, with fewer reinvestment opportunities, will reinvest less and thus grow less. The growth companies aim to internally compound, eventually set to return substantial cash streams to shareholders, only once reinvestment opportunities begin to dry; long-duration. Value, on the other hand, produces cash it has less need for and therefore distributes it now; short-duration.

Yes, that distillation is too simple. Equities are often bucketed together and discussed as an entire asset class or split into the above binary as A and B, but different factors provide radically different sets concerning volatility, correlation, duration, and so on, placing them across wide spectrums. Still, there often appears to be a disregard for those spectrums, as well as a total disregard for the beautiful specific idiosyncracies, and an unhealthy fixation on the tail end of growth. Should that surprise us? Isn’t there a universal understanding that defensively oriented assets implicitly trade away some risk in exchange for lower forward returns? Even so, if your high-scorers appear better risk-adjusted, why would you ever dilute your roster with low-scoring assets? There are several reasons.

If you are correct in your views on a high-growth stock set to produce high returns, those returns usually take time, lots of time; long-duration. Over that period, even the most successful companies run into problems that, at the time, can appear life-threating. Even if they aren’t life-threatening, there is no stopping the market from violently selling off the name. While so many claim to be long-term oriented, it becomes significantly harder to remain so when concentrated into assets, whose present return profiles are primarily a function of share price appreciation, find themselves deeply in the red from time to time.

Equities resembling short-duration provide a form of mental stabilization when taking an active management role. Unlike long volatility, these assets are inherently positive carry rather than negative carry—certain subsets produce at levels that represent a powerful offensive force on either own. Excess cash continually and consistently returned to shareholders can be redeployed into other assets when they become deeply depressed. Further, while lacking the radical convexity profile of long volatility, the capital returns provided by these assets via share repurchases can further enhance offense, as the efficiency of those programs is a function of share price over the repurchase period—a less potent, but still effective form of long volatility exposure when measured over longer periods. With a thoughtful assembly, a portfolio can continually rebound shots at both ends of the court.

While Rodman’s career stats best illustrate his abilities to impact games, December 17, 1996, truly captures his freakish outlier status. That day, the Bulls played the Lakers. The Bulls were behind by 15 points, 72-57, 24 minutes into the game, struggling to contain Shaq, who was leading with 23 points. In the second half, the gargantuan 325-lb Shaq was guarded by Rodman, who was 100 lbs lighter and roughly half a foot shorter. On paper, the matchup appears hopelessly lopsided, yet Rodman’s unwavering endurance and sustained physicality led to Shaq only scoring 4 points in the second half, with only two shots in the fourth quarter and overtime. Despite having been desperately behind, the Bulls ultimately won the game 129-123. None of this is to detract from Shaq's unbelievable achievements—another one of the greats. But what should be highlighted is the return on investment each team generated from these two players. Not only did Rodman produce a staggeringly high adjusted win % differential despite being a relatively poor scorer, but he did so despite being a shockingly affordable asset to the teams he was on. As the adage goes: price is what you pay; value is what you get:

In both professional sports and investing, there are distinct limitations on available resources to fund your team. However, while each NBA team can have only five players on the court at any given time and a capped multiple of that on their bench, investors are provided substantially more creative flexibility in creating their roster. Rodman-like assets are as rare as Rodman, but like Rodman, they are often overlooked, and at times, you may be able to draft them for far under their productive value.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share. To further show your support, consider pledging a paid subscription to Invariant.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment here or message me on Twitter.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

This was an awesome read, many thanks!

Right so if not bonds, cash? These vol strategies are hard to get for plebs like me 😅