Forged by Fire

“Time is the fire in which we burn.” - Gene Roddenberry

Think back to last summer. By almost all measures, markets were red hot, and everyone was fixated on everything going up and to the right.

Companies at x50 sales

Meme stocks

Rampant crypto speculation

SPAC mania

NFTs

It seemed there was a lot of fun to be had, but something didn’t sit right with me. A bit over a year ago, on July 12th, 2021, I wrote the following short essay:

The Nature of Wildfires and the Business Cycle

Nature is a mighty teacher.

One of its most shocking lessons is that perfect balance is a myth. Chaos is mistaken for symmetry. Nothing lasts forever.

We can observe this in prairie lands.

Sometimes slight imbalances compound. It can take months, years, or even millennia. Or a shock, like a drought or a disease, kills off a food source near instantly. Less food means less grazing, which means other plants aren’t kept in check.

Any semblance of equilibrium is lost.

Certain plants just keep growing and spreading. Too many means too much competition for sunlight, soil nutrients, and too few bugs and bees to keep up with it all.

The system peaks.

Some animals get weak, and certain plants disappear. Grasses die and dry out. And then a fire comes.

With enough dried-out vegetation, wildfires spread effortlessly. There’s immense short-term pain.

But it’s not all bad.

This natural process stifles excess, reintroducing it into the soil as nutrients. And with less competition, growth is easier for future generations.

The cycle repeats.

Business cycles are no different.

Capital gets thrown into ventures that are projected to return greater capital. Sometimes, these projects are simply too optimistic. Minor miscalculations multiply until unignorable.

Other times, large, exogenous shocks (like COVID) disrupt the world’s trajectory.

Significant enough shocks mean no one is spared.

Disruptions proliferate quickly.

Failing companies can’t pay vendors, workers lose their jobs, less money is spent, and debt doesn’t get repaid. All of these things cause other businesses to make less money, throwing off their own models.

Rinse and repeat, deep into the trough.

Everyone finds themselves in defensive posture-uninterested in feeling more pain. People hoard their money. That means less spending and less investment into new endeavors because things look bleak, at least in the interim.

They wait until the smoke clears.

So, where are we now? Anyone who claims to know with certainty is a liar.

But there was a lot of dry grass before COVID struck. And COVID wasn’t a wildfire; it was a volcano.

Acting fast, we drowned the world in liquidity to combat potential damage. Now, excess capital and pent-up demand are driving even more growth. But we never let the dry grass burn. We never let nature finish its cycle.

No one knows how long the rain will last. No one can say how thick the overgrowth will become.

Will there ever be another spark?

Or have we beaten nature?

We’re never quite able to see the forest for the trees.

Even now, the financial markets look precariously positioned. Inflation is dominating headlines. Companies are scaling back. Every lackluster quarterly report is blaming macro headwinds. And of course, there are many people, shouting loudly, saying these types of things are very very bad. I’m not so sure. I need to ask: bad for who?

Not all companies are impacted by all things in the same exact ways. As economic pressures crank up, companies are facing higher costs of capital, margin pressures, pissed-off customers, and more. Considering how much dry overgrowth is still left in the system, a few extra sparks could make things a lot worse. But do you know what’s normally left standing after a forest fire? Giant redwoods. Towering over everything else, with huge trunks and foot-thick bark, they can survive for thousands of years—and they see plenty of fire over their lives.

I’m not saying large companies have it easy right now. But I think it’s only natural to expect a greater divergence in relative performance.

Think of all the colossal companies that have been able to maintain their massive investment cycles during the past few years. Does this not lead to them eating their competition’s lunch while everyone else stalls out? You might argue against this idea, citing things such as recent headlines about layoffs at big tech companies, but how much of that was strategic hiring to starve smaller competitors of talent in the first place?

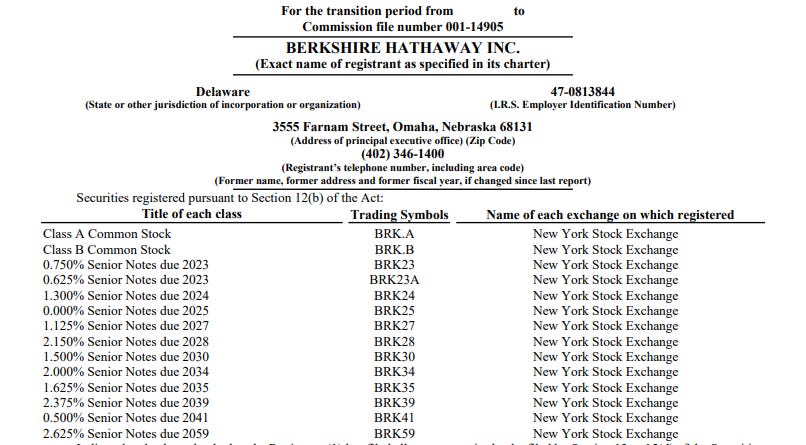

I wasn’t planning on naming specifics, but what about the patient giant? Berkshire Hathaway supports an immense collection of assets, and Charlie Munger famously said, “I’ve never heard an intelligent cost of capital discussion”. Berkshire always seems to be able to negotiate incredibly favorable deals when everyone else is scrambling to get out of the flames, and I suppose I, too, would care less about the cost of capital if I could pull this off:

This line of thinking isn’t limited to redwood-like companies benefiting from gargantuan scale. Across many sectors, there are other operators, relatively smaller, that have formed thick bark and deep roots from growing other competitive advantages. Lawrence Hamtil recently wrote an exceptional piece that touches on the opportunities consolidation can lead to. Isn’t it likely that the current conditions accelerate the rate at which consolidators wrap their roots around the rest of their respective fragmented markets, further entrenching themselves?

This all may be simple, but I don’t think it’s too simple. And sure, there’s always a fire somewhere, so the smoke can make it hard to see what’s what. But isn’t this how it always works? I can’t help but think that hidden in the smoke, fertile ground is forming.

Thank you for reading!

If you’ve been enjoying reading Invariant, could you do me a quick favor?

Please, take a second to like this article by clicking on the heart icon.

Share any of my articles with a friend.

Doing either of these two things helps grow Invariant and allows me to connect with more interesting, curious minds. Thanks again!

Ownership Disclaimer

I may own positions in the companies referenced in this article.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.