“‘They’re only waiting for me to die so they can have my money,’ she would say. ‘But I’ll fool them. I’ll take such good care of myself that I’ll never be ill. They’ll see who laughs last.’” - Hetty Green, Hetty: The Genius and Madness of America’s First Female Tycoon

Hetty Green is as impressive a figure as anyone. Her excelling in finance is especially notable, as she did so when the field was essentially wholly dominated by men and when women were not even allowed to vote. Despite such accomplishments, her name continues to get little mention compared to the industrious male titans of her time. Her life story showcases the blessings and demons that come with a unique obsession with amassing wealth.

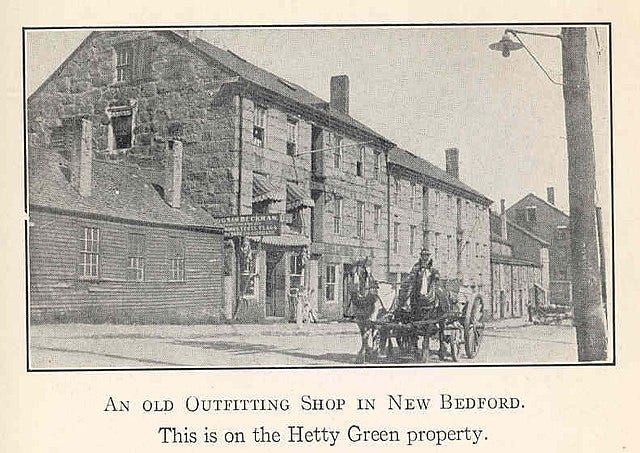

Born Henrietta Howland Robinson on November 21, 1834, Hetty grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. The town was a critical whaling hub and home to Isaac Howland Jr. and Company, where Hetty’s father, Edward Mott Robinson, worked as manager, and her paternal grandfather, Gideon Howland, was partner. Over the first few decades of her life, whaling produced immense fortunes by meeting the fervent demand for the resulting oil—essential for lubricating the rapid industrialization of the country and illuminating its future by way of lantern.

Coming from a family of significant means, it could easily be assumed that Hetty was afforded every possible luxury in her youth. Imagine all of the fine dresses, fragrances, and jewelry; maids and service people to anticipate every need and desire; and a future of attending every gala, ball, and party hosted by other well-to-do families in search of an equally well-to-do husband. That was not Hetty. The Howlands were staunch Quakers, practicing the virtues of simplicity, humility, and hard work. Best portraying their allegiance to thrift, Hetty’s father, Edward, was known to smoke four-cent cigars. Whenever offered a ten-cent cigar or finer, he would politely decline—fearing he would acquire a taste to spend excessively. Hetty, too, had little desire for fine material goods. She showed similar disinterest in socializing and even less in seeking love, as she had already found it in finance through the family business.

Starting at a young age, Hetty made herself useful by reading financial news out loud to her father—everything, including shipping routes, currencies, taxes, tariffs, and traded securities. With the seasoned professional acting as a sounding board, she eagerly learned all she could. It wasn’t more than a few years before she was tracking finances and marking the Isaac business ledger on her own.

As Hetty transitioned toward adulthood, she spent time at several boarding and finishing schools while continuing to assist in managing the family business. Then, coaxed by her Aunt Sylvia to find a husband, she moved to New York City, not without hesitation. Provided a modest allowance for living expenses, she lived in a dismal apartment and spent little time or money on her physical appearance or hygiene, instead opting to invest the majority into bonds.

Hetty returned to New Bedford. The widespread adoption of petroleum caused a violent drop in the demand for whale oil. Fortunately, Hetty’s father had exited the industry prior to the collapse, diversifying assets into banking, trade, and retail, amongst other endeavors.

In June 1865, when Edward died, Hetty was the sole beneficiary of the estate. She received roughly $900,000 in cash, and a remaining $5 million was bound into a trust, to which Hetty received the earned income. While hardly a position to complain about, she was livid that the bulk of her father’s fortune was tied to a trust in which administrators collected fees for managing, generating returns far under what Hetty believed she was capable of if she had full access to its entirety.

Merely a few weeks after Edward’s death, in July, Sylvia Ann Howland, Hetty’s aunt, passed away at the age of fifty-nine after lifelong suffering from a spinal deformation and other ailments, leaving a $2 million estate. Hetty expected to receive the entirety since she and Sylvia had previously drafted their wills together. However, toward the end of her life, Sylvia drafted a new will with the help of the doctor looking over her, presenting several surprising and concerning considerations. Firstly, toward the end of her life, Sylvia was frequently administered various painkillers and other mind-altering medications. If that wasn’t enough to bring into question the validity of the new will, it should also be noted that only half of the estate was set to go to Hetty, structured into a trust in which she would receive only the earned income, similar the trust established for the bulk of her father’s assets. The remaining $1 million of Sylvia’s fortune was set to be carved up, partly dispersed to several charitable causes, and the remainder placed into a number of small trusts designated for family friends, local widows, and Sylvia’s medical team—including a tidy sum set to go to the doctor who helped draft the new will.

To Hetty, the circumstances surrounding her aunt’s new will were suspicious. And again, the idea that her inheritance be held in a trust, which she felt was likely to produce substandard returns, was offensive. On top of this was a factor more untenable. The doctor who had helped Sylvia draft the new will, who was set to receive a small portion, was also established to help oversee Hetty’s trusted portion, entitling him to extract annual fees. Thus began Hetty’s legal offensive, contesting the validity of the second will.

Hetty’s contestation was also deeply problematic. For one, upon review, it was apparent that a team of reputable lawyers expertly drafted the new will—it appeared bulletproof. The legal proceedings tied up Sylvia’s assets, denying funds desperately needed by the local widows and other beneficiaries for years. In the midst of the fallout, there is a record of Hetty attempting to bribe a judge to have her trusted portion all go directly to her—for which she was lucky she did not land in jail. More concerning, introduced into court evidence was a supposed addendum to Aunt Sylvia’s initial will, invalidating all future wills and ensuring the entirety of her fortune would go to Hetty. However, the signature of the addendum was strikingly similar to the signature found on the first will itself—so identical, despite the frail Sylvia barely able to hold a pen, that the only logical conclusion is that it was a forgery.

Ultimately, Hetty lost her court case to toss out the second will. During the long-drawn-out ordeal, Hetty married Edward Green, one of her only allies at the time. Green was also a millionaire, having worked for a successful trading house, conducting critical business for the firm in Asia for a time. Worried that Hetty may face charges for the forgery in the case of Sylvia’s will, the couple moved overseas to England for a period.

Apart from having substantial wealth, Edward Green shared little similarity to his wife. He was sociable, outgoing, loved to spend lavishly, always aimed to be the life of the party, and aggressively tipped wait staff. Early in their marriage, Hetty’s financial prowess was largely overshadowed by her Husband’s. But that would not last. He also invested aggressively, ultimately losing the majority of his fortune through speculation—needing to be bailed out by his wife, leading to a long period of estrangement. For Hetty, such carelessness with capital was a betrayal, and her primary love remained finance.

Hetty made several notable investments throughout her life. But before deploying a dollar, she obsessively scoured and attained all available information on any potential opportunity. Having first received a portion of her father’s estate in cash, she poured the majority into United States greenbacks, which had been printed ad nauseam to cover the costs incurred following the Civil War. The notes were deeply discounted, trading at less than half of their original value, reflecting uncertainty around the government’s ability to satisfy its obligations. But with rapidly growing efforts to capitalize on its vast natural resources, the country prospered, as did Hetty.

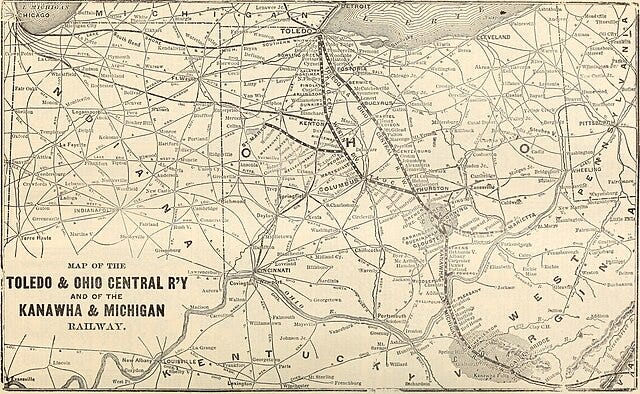

Hetty Green began to branch out, selectively investing in a number of railroads that were laying tracks to connect the blossoming country. Other parties, namely banks, had conducted far less due diligence in railroads, overlending to numerous projects, often to people with little operating history or expertise. Associated bonds dropped to nearly worthless, and in 1872, several large banks failed, leading to the panic of 1873. While most panicked, Hetty did not—always keeping a large pile of cash at hand and refusing to use leverage. She was personally responsible for bailing out banks, rails, and even, once, New York.

Throughout the rest of her life, Hetty’s conservative approach allowed her to not only survive economic cycles but thrive. With the wealth she had directed, alongside substantial income generated by her trusts, Hetty continued to amass a hoard of bonds and other listed securities. She also avidly scooped up real estate—entire blocks in New York, Chicago, and other cities—leaving them completely undeveloped to keep costs, especially property taxes, low, happily sitting on them for decades. Summating her investing philosophy, one quote of her rings louder than all others:

I buy when things are low and nobody wants them. I keep them until they go up and people are crazy to get them. That is, I believe, the secret of all successful business.

There is another side to the story of Hetty Green, the woman who amassed untold wealth. Sometimes described as miserly, cheap, or thrifty, few words truly capture her obsession with accumulating capital. In fact, the only thing she opened her pocketbook to freely was the endless stream of lawsuits she launched against countless enemies throughout her life who she accused of financial wrongdoings. Her net worth, at the time of her death in 1916, was $100 million—approximately .2% of Gross National Product (and worth billions today). Yet, throughout life, she was known to wear only old, black dresses, keeping them until they were so ratty she was forced to buy another. She would buy small, old cuts of meat from the butcher, arguing anything beyond that was extravagant. When needing miscellaneous items, she was known to spend untold hours haggling with shopkeepers over items priced at just a few cents each. There is even one account of Hetty, carrying a heavy bag of bonds to deposit into her bank, worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, walking through the streets of New York rather than paying the fare for a carriage. Perhaps the most egregious of her behaviors, she was known to dress herself and her two children in rags to attend free medical clinics, attempting to get free care rather than paying the rightful price of service—taking away precious time from the volunteering doctors who could be assisting those truly less fortunate.

Could Hetty Green’s drive be tamed or changed, or was it simply hardwired within? She had a fortune, but did she live a truly prosperous life? Undoubtedly wracked by some semblance of guilt when reflecting later in life, she was not known to make a big name for herself with large donations to charities but did likely make numerous anonymous donations to various hospitals and other facilities. The best glimpse into the psyche of the wealthy but lonely woman is provided by the relationship she had with her beloved Skye terrier, C. Dewey. Dewey had no concept of money. He would love Hetty, and she could return love unconditionally without worrying that he had an ulterior motive to get after her fortune.

There are numerous writings on Hetty Green’s life and accomplishments. If her story has piqued your curiosity, I highly recommend Hetty: The Genius and Madness of America’s First Female Tycoon by Charles Slack. It is the fullest, most detailed account of her life that I have found.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share. To further show your support, consider pledging a paid subscription to Invariant.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Very interesting post. It’s the first time I read about Hetty Green.

I couldn’t help but think about Warren Buffet, perhaps because the Berkshire Hathaway textile mills were also located in New Bedford, or because he’s now worth 0.5% of US GDP, in the same ballpark as her 0.2%.

Do we know what motivated her to accumulate so much wealth? Reading The Snowball, it seems that Buffet had extremely poor self esteem when he was young, and having more money served as a “scorecard” of both his financial and personal worth.

The second reason Buffet continued investing and buying businesses even after he was wealthy was that he thoroughly enjoyed reading financial documents, talking to his many financial partners, and getting the best deal in all his business dealings. Were there similar motivations in Hetty?

Typo: “Hetty’s financial prowess was largely overshadowed by her Husbands”