“If everybody is doing it one way, there's a good chance you can find your niche by going exactly in the opposite direction.” - Sam Walton

Bigger isn't always better, yet investors won’t stop obsessing over things like Total Addressable Market. The faulty reasoning begins with the premise that large profits must come from large markets. This is assuredly false.

Not all parts of a market are serviceable, and even if they are serviceable, there is no guarantee that such activities can be done profitably. It must be understood that large markets invite a large amount of competition and, generally speaking, if you want to make a lot of money, competition is bad. Time and time again, we’ve seen competitive pressures erode excess profits until most participants become mediocre.

Instead of wanting to be a big fish in a big lake, why not aim to be the biggest fish in a small pond? Or what if you could be the only fish?

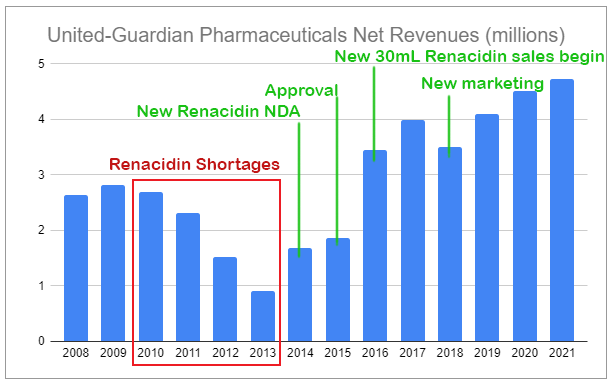

Last week’s piece covered microcap United-Guardian (UG), the largely unknown company that researches, produces, manufactures, and markets products such as cosmetic ingredients, medical products, and proprietary industrial products. It also has two pharmaceuticals, one of which is Renacidin. As highlighted in my previous piece, Renacidin experienced severe shortages during 2010-2014, as it was being manufactured by a major U.S. company that had run into regulatory issues unrelated to Renacidin but nonetheless suspended production. These issues were resolved in 2014, and United-Guardian initiated an agreement with a new supplier and also submitted an application to the FDA for a new product version—a 30mL single-dose container.

I am fascinated by Renacidin, and in my piece, I made a fairly bold claim:

Most important is what I consider the true moat of this portion of the business:

While the total sales and profits generated by Renacidin are impressive for United-Guardian, it is a drop in the bucket compared to the total of the pharmaceutical industry. There are competing products for certain indications, however, if potential entrants were interested in competing DIRECTLY against United-Guardian’s Renacidin brand, the associated costs and risks of doing so, especially the regulatory hurdles, are significantly greater than the potentially available profit pool.

Renacidin is unlikely to ever have a giant market share. But it doesn’t need one to contribute meaningful returns for United-Guardian’s shareholders. Increased awareness boosting sales paired with modest pricing can likely produce very impressive results. I believe that the success of the newest version of Renacidin continues to be overlooked by the market. This is a growing, highly-profitable, niche pharmaceutical that now makes up a significant chunk of sales for United-Guardian.

Renacidin has long been off-patent, yet there is no challenger in sight. From United-Guardian’s 2007 10-K Filing:

The Company's patent on its RENACIDIN IRRIGATION expired in October 2007. The Company does not believe that the expiration of that patent will have a material impact on the Company's revenues.

Why is no one interested in competing directly with it? Where is the generic?

Those are good questions, especially since there have been numerous impactful legislation over the last century leading to the heavy promotion of generic drugs.

In 1888, the American Pharmaceutical Association created the National Formulary. Then there was the Federal Food and Drugs Act, followed by the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), the Durham-Humphrey Amendment, the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments, and the Medicaid and Medicare amendments to the Social Security Act.

All of these, to varying degrees, aimed to make drugs safer and more accessible. But the most monumental legislation focusing on generics was the 1984 passing of the Hatch-Waxman Act, formally known as the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act. This legislation established the modern approach to generic drug regulation. It heavily supports generic creation by providing a variety of incentives to companies that file ANDAs (Abbreviated New Drug Applications), such as certain legal protections, as well as reducing the financial and time costs of producing generics by removing mandates to produce animal (preclinical) and human (clinical) studies like brand-name drug are required in order to establish safety and effectiveness. Currently, the approval of generics mostly focuses on making sure that relative to the reference listed drug (RLD):

The generic drug is the same type of product

The generic drug has the same active ingredient in the same amount

The generic drug has the same release mechanism

Manufacturing can be done correctly and consistently

The container and packaging are entirely appropriate

The version is stable and only deteriorates after a reasonable amount of time

Labeling is the same as the Brand’s name

Relevant patents or legal exclusivities are expired

Generic drugs must prove to be bioequivalent to branded drugs based on scientific evaluations. The only differences generic drugs are allowed are shape, color, flavorings, and different inactive ingredients.

Since 1983, the number of top-selling branded drugs with expired patents that have generic competition has grown from 35% to ~85% today. This rise of generics is largely a boon to consumers, who save billions in the United States annually, with data showing that the market entry of a single generic competitor can reduce the cost of a drug by over 30%, and multiple generic competitors can drive prices down by as much as 85%.

It’s worth applauding regulations that have made it cheaper and faster to get drugs to market, but cheaper and faster are relative terms and don’t necessarily mean cheap or fast. Since the FDA maintains an imperative interest in ensuring that generics are safe, the review processes for not just entirely new drugs but also generics are incredibly robust.

Entirely new medicines can cost over $2 billion and take longer than a decade to discover and develop. Establishing biosimilars can cost an estimated $100-250 million and take 5-9 years. Small-molecule drugs, which are what most available drugs are, including Renacidin, are far less complex. Nonetheless, small-molecule generics usually require several million dollars and several years leading up to FDA approval.

Beyond that portion of the process, a would-be producer must weigh additional regulatory costs, legal risks, continued manufacturing, distribution, and market dynamics, along with a clear forecast of potential revenues and profitability.

The below model is a simple approach to estimating the net present value of Renacidin for United-Guardian and how the profit pool would change with a generic entrant. The gross sales were based on UG’s FY 2021 reported results. All other inputs were estimated based on publicly available data.

Some pretty big assumptions were made that weigh in favor of the generic:

It’s assumed the generic is able to immediately steal 80% market share through pricing discounts when initially marketed.

The generic is provided a 100% chance of eventual regulatory success.

There’s no given threat of other therapeutics for the same indications.

Yet, while a generic entrant would assuredly destroy Renacidin’s profit pool for United-Guardian, using a range of realistic hurdle rates indicates that there is no conceivable way a generic entrant would see a positive return on investment.

Granted, the above math is incredibly simplified and in terms of precision is akin to scribbling on the back of a napkin after blowing one’s nose with it. Since it’s not intended to be precise, nothing is off-limits, and you should be able to protest some of the numbers. You could argue that Renacidin is poised to experience elevated growth and will not reach a terminal state until far into the future. You could also criticize the presented market shares, pricing, margins, delays, and terminal growth rates. It should also be easy to point out that there may be other qualified incentives through various recent legislation. And on top of all that, there are numerous large, multinational generic drug producers who could manufacture a generic more cost-effectively than anyone else, and, critically, have extensive experience navigating the regulatory process and could potentially save substantial time leading up to a generic’s approval.

Those are all reasonable points, but they are all dwarfed by the fact that the most significant deterrent has not yet been factored in:

The FDA further incentivizes generic competition by rewarding eligible First Generics with a 180-day marketing exclusivity period.

Enter: Authorized Generics

A major barrier that a would-be generic producer must assess is the likelihood of the brand drug company introducing an Authorized Generic (AG). AGs are the exact same as branded drugs because they are the same identical products but simply use different packaging. An AG can enter the market using the existing already-approved NDA without filing a new ANDA. This is faster, cheaper, and critically, bypasses any 180-day exclusivity period granted to a First Generic.

With an AG, United-Guardian’s total profit pool would still be materially diminished, but it would retain substantial market share. By my math, this single aspect alone means Renacidin’s total profitability would have to be vastly larger to invite competitors.

To reinforce this notion, this past week, one of United-Guardian’s executives was kind enough to lend a few minutes over the phone. The pertinent part of our conversation went as follows:

ME: The patent for Renacidin expired in 2007. It does not appear there is a generic competitor, and your company (United-Guardian) does not produce an Authorized Generic. Is that correct?

UG EXECUTIVE: That’s correct.

ME: My understanding is that the lack of generic competition stems from the fact that the total addressable market is small and the profit pool theoretically available to a generic entrant is far too small to be viable. Is that correct?

UG EXECUTIVE: That’s correct.

ME: I would assume that you’re unable to disclose any information regarding United-Guardian’s internal estimates on what it would take to entice a generic competitor?

UG EXECUTIVE: That’s correct. I cannot disclose that kind of information.

Could things change in the future? Of course—especially with potential additional legislation further incentivizing or subsidizing generic production. But for now, the most likely outcome is for the current dynamics to persist.

I have no horse in the race (yet), but I’m thoroughly enjoying watching from the sidelines. If you haven’t yet, go back and read the full analysis, valuation, and pricing of United-Guardian. You’ll get a lot out of it if you enjoyed this piece.

Thanks for reading!

Ownership Disclaimer

At the time of publishing this piece, I have zero positions in United-Guardian. I may initiate such positions in the future.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Tags: UG 0.00%↑

Additional Resources:

What Is the Approval Process for Generic Drugs? Source

Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book. Source

FDA User Fees to Rise and Fall as New Fee Agreements Move Forward. Source

Generic Drug User Fee Amendments. Source

Generic Drug Applications: FDA Should Take Additional Steps to Address Factors That May Affect Approval Rates in the First Review Cycle. Source

How Obama’s FDA Keeps Generic Drugs Off the Market. Source

Let’s See How Biosimilars are developed. Source

Generic Drugs in the United States: Policies to Address Pricing and Competition. Source

Parsing the Generic-Drug Approval Process. Source

Overview of the Hatch-Waxman Act and Its Impact on the Drug Development Process. Source

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics as of July 1, 2022. Source

Biologics vs. small molecules: Drug costs and patient access. Source

The Economics of Biosimilars. Source

FDA Generic Drug Rejection, Approval Rates Tell a Conflicting Story. Source

Medicare Part D: Competition and Generic Drug Prices, 2007-2018. Source

Renacidin - Product Information. Source

FDA Product-Specific Guidance search. Source

2021 First Generic Drug Approvals. Source

Generic Drug Price Tags: Too High. And Too Low. Competition Can Help Create an In-Between. Source

Generic Drug User Fee Rates for Fiscal Year 2022. Source

Martin Shkreli is good at niche pharma. eg PKAN is estimated to affect only about 5,000 people worldwide but he found a quicker route to approval as FDA isn't as hard with low TAM diseases so the moat might not be as big as we think but needs a niche generic expert :)