Schlitz's Souring

“Schlitz. No Schlitz? Blatz. No Blatz? Improvise.” - Lt. Col. Frank Slade (Al Pacino), Scent of a Woman

Easter weekend is upon us. For those who don’t celebrate the holiday in the traditional sense, many still happily worship the bunny as a reason to get together with family. But no matter the holiday, and irrespective of what food is spread across your table, no celebration is complete without the right drinks. I was reminiscing with family, and someone brought up a name none of us had thought of for quite some time:

“Schlitz.”

The brand of beer is still produced today, but many consumers are unfamiliar with it. Affinity for the brand primarily resides here in the Midwest, closer to where it originated. Chances are, most people are even less familiar with the brand’s colored history. From its launch to becoming the most popular beer in the United States, and then its eventual downfall, Schlitz offers timeless lessons—and warnings—on brand management.

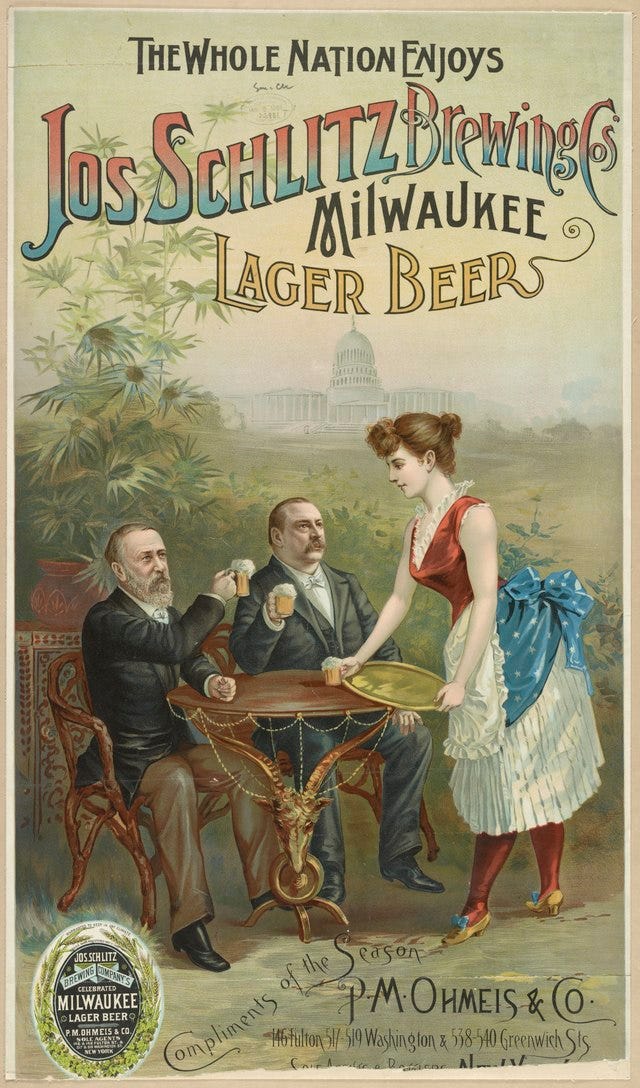

In 1849, August Krug, a German immigrant and reputable owner of a small restaurant, started a brewery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which was home to other brewers that would go on to become household names. In 1856, at the age of only forty-one years old, August died as the result of a terrible fall. Replacing him at the head of the brewery was Joseph Schlitz, whom August had hired as a bookkeeper prior. Two years later, Joseph married August’s widow, Anna Maria Krug, and renamed the business the Jos. Schlitz Brewing Co.

Schlitz Brewing was a respectable outfit, but it was relatively small in stature. Its team was comprised of a limited number of people, including a handful of brewery workers from Bavaria. However, that would all change in October of 1871, when the Great Chicago Fire destroyed essentially all major brewing operations in the city. Schlitz’s lager recipe was a crisp, slightly sweet blend, sporting distinct hoppy notes without heavy bitterness. It stood out compared to the tamer products of competitors, and its widespread appeal would be proven when the company began to leverage Chicago’s trains to expand its distribution.

Despite Joseph Schlitz’s vision for the company, he only witnessed a sliver of its success, as he died in 1875 when the ship he was on sank, leaving no survivors. Taking up the reins were his nephews, the Uihlein brothers, who opted to keep the company name unchanged. The Uihlein family would head the business for over a century. They focused on quality ingredients, paired with continued investment in improved manufacturing efficiency and capacity. Beer consumption rose steadily, and Schlitz was at precisely the right place to capitalize. The company’s production in Milwaukee had grown from 4,400 barrels in 1865 to 70,000 in 1875. But that was only the beginning.

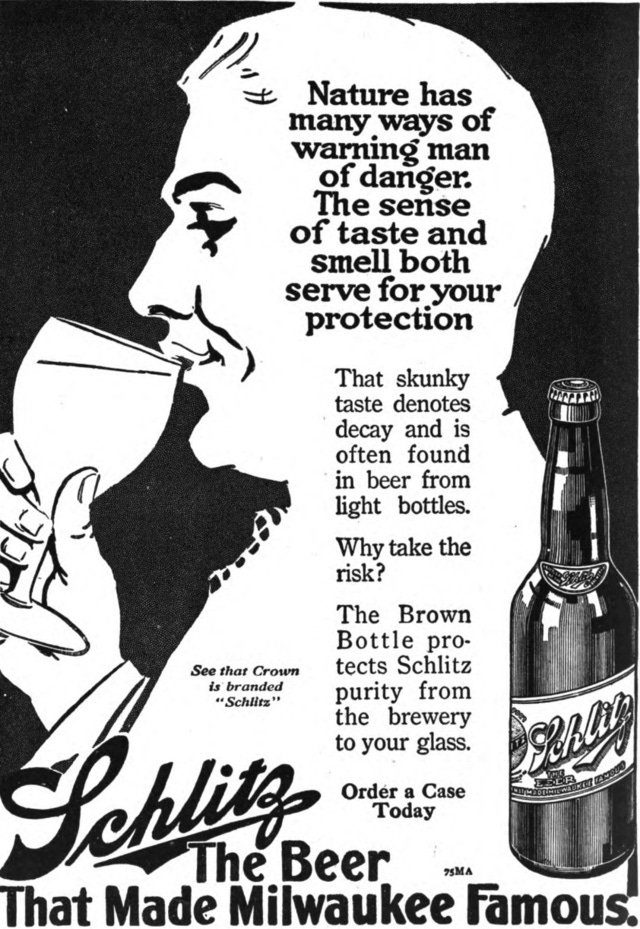

By 1902, Schlitz had outpaced fast-growing competitors to become the largest brewer in the United States. Its growing profits allowed it to improve operations, increase marketing, and innovate continually. In 1912, the company introduced the brown glass bottle, which protected the beverage from sunlight, reducing spoilage and preserving the beer’s flavor. All other major brewers followed, quickly adopting similar bottles to protect their products and avoid being seen as inferior.

After experiencing decades of success, Schlitz’s outward expansion met a roadblock in 1920, when prohibition was enacted in the United States. To maintain the use of its workers and manufacturing capacity, the company retooled some of its systems to produce milk chocolate. Although this pivot allowed the company to stay afloat, its confectionery products gained little traction, struggling against Hershey’s. These efforts were discontinued in 1928.

Milk chocolate, gumballs, and hard candies were not the only pivot the company made. Alongside malt extract, Schlitz began selling non-alcoholic soft drinks. This allowed the company to maintain much of its original infrastructure, with the expectation that prohibition would not last indefinitely. Fortunately for the company, their assessment was correct. When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, and with many other brewers having closed shop, the company resumed beer production and quickly rose to the top of the industry.

During the mid-1930s, Schlitz held the title of the world’s top-selling brewery. However, such a title was one that it was unable to hold onto indefinitely. Increasing competition from other hubs across the United States, where brewers paid their employees higher wages, led to a multi-month strike in Milwaukee in 1953. Labor costs continued to increase, and the company eventually faced pressure from rising ingredient costs, too, which depressed profitability as volumes continued to rise. Beginning in the late 1960s, the company replaced several key ingredients in its lager. The substitutions were substantially cheaper, aiding the company’s margins. But they also changed key characteristics of the product, including its flavor.

In 1976, the brewer grew mindful of potential changes proposed by the Food and Drug Administration, in which manufacturers would be forced to disclose all ingredients on product labels. To avoid revealing its questionable, low-quality ingredients, Schlitz again changed its recipe and production processes, resulting in numerous issues, including a significant product recall. Consumers grew more dissatisfied with the company and its hallmark product, converting to other brands, including those of Miller and Budweiser.

The company believed reverting its product formula was unviable, as the associated costs would be disastrous to profitability. Instead, in the late 1970s, the company intensified its marketing efforts, with a particular focus on TV ads. Not only were those ads ineffective, but they actually alienated consumers from the brand further. The company saw its position fall from first to second to fourth. Its problems would be amplified by another significant strike, this time in 1981, lasting four months.

The impact of Schlitz’s misteps and the strike left the company crippled. Later that same year, the failing company opted to explore selling its remaining operations. In 1982, the Stroh Brewery Company acquired Schlitz. It consolidated manufacturing, expanded offerings, and repositioned those products in select markets, aiming to turn the business around. Those efforts were ultimately unsuccessful.

To make matters worse, Stroh had taken on a gigantic debt burden to finance the acquisition. This resulted not only in the acquired business failing, but also in the entire Stroh enterprise following suit. In 1999, after the Justice Department concluded its antitrust review, Stroh sold its beer brands and assets to Pabst and Miller.

The tale of Schlitz is undoubtedly a sour one. Fortunately, for those who drink the product today, Pabst reverted to the original recipe in 2008. Part novelty, part nostalgia, the namesake beer, which once held nearly 20% of the domestic market, now makes up a tiny fraction.

Can you think of any potential parallels to the present day? Consumer packaged goods companies have faced numerous hardships over recent years. The pandemic shook supply chains while introducing tremendous uncertainty toward consumption patterns. Inflation in input costs continues to race against recognized operational efficiencies. Countless brands have not only aggressively raised prices and reduced product sizes but also made creative “new and improved” adjustments to formulas. Without honoring the relationship between product and consumer, no brand is immune from becoming the next Schlitz.

Thanks for reading. Enjoy this piece? Hit “♡ like” on the site and share it.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.