“Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.” - Charlie Munger

Is ESG-driven investing good or bad? How you answer is dependent on how you define ESG and your objectives. It’s certainly good for the pocketbooks of its largest promoters. Beyond that, results remain dubious.

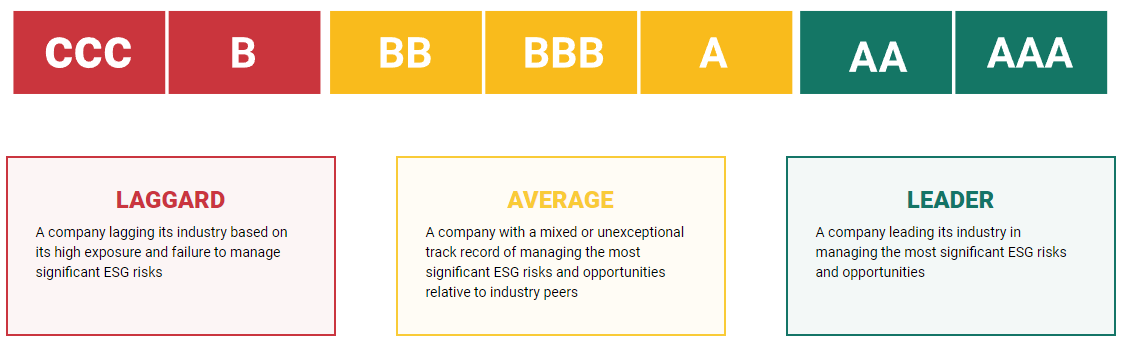

Broadly, ESG-driven investing aims to consider environmental, social, and corporate governance risks in an investing framework to produce positive outcomes. If that seems vague and wordy to you, it should. There is no standardized definition or methodology—only a vast number of agencies, firms, and funds using disjointed approaches to incorporate non-financial considerations into financial decisions.1 Unlike the stringent requirements associated with financial reporting, much of the ESG data utilized is unregulated. Even worse, conclusions are often presented to imitate regulated data, such as credit ratings, as illustrated by MSCI’s ESG ratings below.

The range above is designed to be easily understood, with a green AAA being definitively good and a red CCC assuredly bad. But these ratings are relative to industry peers and are not to be measured across industries or in absolute terms. As such, a more positive rating can reflect the better of a bad bunch rather than an implicit good. Even less clear, these ratings don’t explicitly reflect a company’s impact but rather the impact of ESG risks on the company’s performance. And despite the first letter of the acronym standing for environmental, many investors would be surprised to learn that this scoring system does not reflect climate risk or climate rating. Further, as agencies have varied approaches, including unique variables and weightings, as well as non-uniform goals of what they are measuring, the task of making normalized comparisons across ratings is ensured to be virtually impossible. Under the gauge of proprietary, understanding certain methods remains elusive—ironic as a common variable across rating approaches is factoring transparency and disclosure practices.

Something suspiciously uniform across agencies, however, is a claim that their own unique ratings can assist investors in assessing risk and opportunities, leading to enhanced returns. But research shows the exact opposite, with firms that score lower on ESG indicators exhibiting higher returns2 and ESG funds underperforming other funds within the same asset manager and year, despite higher fees.3 Beyond academic research, this can be explained intuitively. To start, any factor representing a material financial risk to a firm can and should be included in traditional business, financial, and securities analysis—there is simply no need to create a new category, ESG, aside from incentive to market. Since ESG-driven investment approaches wield non-financial considerations, they mathematically and implicitly limit investment pools while disregarding potential returns—promising outperformance remains impossible.

None of this is to say that investors shouldn’t care about specific issues dear to them. Investors should strive for a more nuanced approach to evaluating companies and investments. However, unlike financial metrics, in which there are clearly accepted ways of measuring, many aspects of ESG remain brutally difficult to objectively define.4 That difficulty leads to the less thoughtful approach of outsourcing any sense of responsibility, limiting positive engagement while generating an ever-growing list of investors wholly divesting and avoiding specific industries. But, along with handicapping returns, attempting to pressure public firms by reducing investor appetite simply pushes associated industries toward private funding. No matter whether new entrants are funded privately or existing public entities are taken private, both assure a drastic reduction in transparency, disclosures, and opportunities to engage as stakeholders.

While many proponents of ESG claim such initiatives will revitalize and invigorate capitalism, they may be doing so in the most unintended way. Just as the proliferation of passive investing flows reduces the number of active participants in financial markets, ESG-based activities further warp the functions of price discovery and capital flow. Fundamentally, if one (growing) bucket of investors is willing to sell certain assets regardless of price and unwilling to buy regardless of prospect—anyone inversing such an approach is welcoming greater opportunities. Edge is difficult to acquire and fleeting, but ESG may act as one, creating anti-bubbles for the discerning to seek.

Hitting “♡ like” and sharing this piece are unintended outcomes of ESG.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment here or message me on Twitter.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Berg, Florian, Kölbel, Julian F., Rigobon, Roberto, 2022, Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Source

Ciciretti, Rocco, Dalò, Ambrogio, Dam, Lammertjan, 2022, The Contributions of Betas versus Characteristics to the ESG Premium. Source

ESGiggles.

Interesting read. Great job summarizing the issues of an extremely nebulous topic. Are there any positives to ESG? Or is it so confusing by design? (I.e. exploit good intentions to influence large investors). Thanks!