Toxic State

“Inside every cynical person, there is a disappointed idealist.” - George Carlin

On September 29, 1982, Mary Kellerman died shortly after taking Tylenol.

She was 12 years old.

That same day, Adam Janus (27) died after taking Tylenol. His brother, Stanley (25), and Stanley’s wife, Theresa (19), later also died after having taken from the same bottle. Over the next several days, this trend continued, with Tylenol-related deaths popping up all around the Chicago Metropolitan area.

Lab tests would expose the presence of cyanide in the tainted bottles, followed by investigators concluding that while the bottles were safely produced, they had likely been tampered with once on store shelves. The manufacturer of Tylenol, Johnson & Johnson, issued warnings to distributors and hospitals and halted all advertising. But copycats began to spring up. Targeting Tylenol and other over-the-counter medications, additional deaths occurred across the United States. This led to a voluntary nationwide Tylenol recall, removing over 31 million bottles from circulation. Johnson & Johnson was largely hailed for its response to the emergency, having been highlighted in articles at the time stating its actions were exactly how big businesses should act during a crisis. Despite the praise, the company ultimately settled multiple lawsuits related to the original Chicago area deaths for an undisclosed sum.

The offender(s) responsible for the original Tylenol murders were never found, and after decades of failed inquiries, the investigation has gone cold.

I have a weird habit of thinking about the Chicago Tylenol murders every time I’m aching and reach into the medicine cabinet for relief. Yet, despite the initial deaths all occurring within a mere hour of where I live and the perpetrator having never been caught, I’ve never hesitated to pop the recommended dose. I doubt anyone else in the United States hesitates much either. We have regulations to thank.

In late 1982, the Food and Drug Administration introduced new rules requiring nonprescription drugs sold in the United States to be in tamper-resistant packaging. This would be adopted by the food industry and for other consumer products as well. Unsurprisingly, manufacturers overwhelmingly supported such regulation. It was relatively cheap for them to adjust their production methods, removing them from all kinds of potential future liabilities. All the tough-to-open twist tops, foil seals, and extra bits of plastic that we deal with are the result of these legislative actions. For us consumers, being slightly inconvenienced to avoid things such as acute cyanide exposure seems like more than a fair tradeoff.

The above saga is just one of countless in which the FDA successfully reacted, creating positive regulation in the wake of tragic events. Such actions have also provided the administration with considerable goodwill from the public, leading to its scope and oversight widening. Unfortunately, not all of its activities have been so worthy of praise, and in one specific regard, regulation of tobacco and nicotine products, the FDA’s recent behavior can be marked as deeply problematic.

On December 18th, 2023, the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) announced a new five-year strategic plan. With commitments to timeliness and advancement of operational excellence, there is something painfully ironic in the fact that the five-year plan took nearly a year to form. More concerning, worth a double-dose of skepticism, are several of the administration’s other commitments within the released statement. Specifically, desired outcomes related to several of its goals appear destined to further promote a toxic state of discourse.

Think of the children™

Rationalizing any regulatory action, good or bad, is easy when you paint an alarming narrative. No matter how far detached from reality your plan is, telling people that future generations are doomed is the perfect way to capture attention. “Think of the children™” is the battle cry to chant to drum up droves of public support. It is no surprise that data continues to be presented in a way that convincingly suggests an epidemic of underage users of tobacco products. Such alarmist rhetoric should be disregarded after one considers the facts.

In 2022, Brian King, Director of the FDA’s CTP, held a meeting with the American Vapor Manufacturers, in which he acknowledged:

I will say that I’m an epidemiologist by training, so I’m fully cognizant of the definition of an epidemic which is unprecedented increases over what you’d expect at Baseline. That said, I think and know that the science has shown a decline in the number of youth users and that's a good thing over the past couple years. We have seen declines since the peak in 2019.

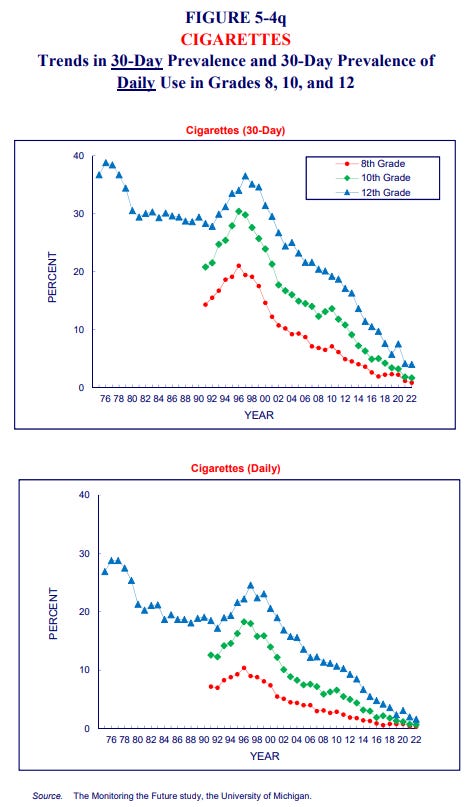

This is further supported by data from the recently published 2023 National Youth Tobacco Survey, showing the number of youths using vaping products daily has continued to decline at a precipitous rate, falling by more than half in the last 4 years. In 2022, during the meeting with the AVM, Brian King also insisted there remains a gateway from vaping leading to cigarette use. While there may be some relationship, such a gateway most certainly is not visibly reflected in the number of high schoolers who use cigarettes—a figure that continues to collapse:

Such trends are promising, but this does not mean efforts end here. The government has an imperative interest in further preventing underage use—a notion I have yet to find anyone in opposition to. In its new five-year strategic plan, the CTP lists a specific Outcome, Violative tobacco products, particularly those that appeal to youth, are not in the marketplace. This obsession over products it views as appealing to youth is, assuredly, the wrong angle from which to attack the problem.

Innate aspects of adolescence include curiosity, experimentation, rebellious behavior, protesting authority, and, of course, a desire to act and appear older. Rather than asserting that the underaged are drawn to vaping specifically due to flavors like bubblegum and cotton candy, it can just as easily be argued that they’re temporarily giving into social pressure to try something new, or that they simply want to partake in activities that are clearly defined as adult. This is not new and it certainly is not unique to tobacco and nicotine. What is unique, however, is the widespread fixation on flavors and the proposition of banning most varieties of tobacco and nicotine products. It is also bizarre. You do not see widespread calls for banning flavored alcohol to curb underage use—imagine the hoards of angry adults protesting such measures, worried their favorite libations will be pulled from shelves. Likewise, for substances far less controlled, imagine a similarly silly approach to reduce youth obesity by banning cheese as a characterizing flavor ingredient of burgers and pizza. Dinner is ruined.

At the same time, there is a relationship between flavors and the availability of vaping products to youth. The FDA, through its various authorization processes, has denied every vaping product that includes non-tobacco characterizing flavors. In the U.S., the group of companies commonly referred to as Big Tobacco does not currently produce any such products other than tobacco and menthol flavors. Rather, those highlighted as the source of proliferating youth use appear to be predominantly manufactured by foreign parties, imported, and sold through various independent retail outlets that have far lower adherence to 21+ age verification policies. Many of those same foreign manufacturers show little interest in following the time-intensive and capital-prohibitive process of having their products authorized through the FDA’s Premarket Tobacco Product Application program. At the risk of sounding apologetic, it is somewhat understandable why companies are disinterested in engaging in such a process. Even major corporations that have been willing to jump over the highest hurdles set by the government have received marketing denials for their products, only to then go through an additional burdensome process of legal challenges, in which courts have found the FDA’s actions to be arbitrary and capricious, having moved goal posts and behaved inconsistently. Regardless, an appropriate solution to further curbing underage usage is to increase enforcement actions and to ensure higher compliance rates to verify age at the point of sale. Presently, Synar provides states with a target rate of 80% compliance. Framed differently, this permits up to 20% of tobacco sales to minors before being found in non-compliance.

Regarding enforcement actions against illicit products, the FDA is beginning to scale to a greater degree—something I hypothesized earlier in the year as an outcome following a scathing independent report highlighting the administration’s woeful inefficiency. But, in all, efforts still appear wholly unserious. The trickle of warning letters issued throughout the year is a drop in an ocean of infractions. To those disinterested in following the law, further violations leading to Civil Money Penalties, which carry a maximum cost of ~$20,000 for a single violation, are merely an expected value calculation and cost of doing business. The FDA becoming more serious is required before violators follow suit.

In the interest of appearing serious, the FDA also recently announced the completion of a joint federal operation alongside the U.S. Customs and Border Protection that seized 1.4 million units of “illegal youth-appealing e-cigarettes” carrying a total value of $18 million. The numbers sound large and impressive, but this effort took multiple months of preparation and, by my math, represents a sum of illicit industry volume that is likely to have nearly zero effect on availability at the retail level. As one of the FDA CTP’s objectives in its strategic plan is to Ensure the most efficient and effective use of financial resources, we can only hope that the processes in place and learnings from this first joint operation will make subsequent endeavors far more expeditious. Stepping back, concerning the use of government resources more broadly, one must consider opportunity cost. Just as the government and various organizations track tobacco and nicotine usage, there is an ample body of data related to rates of youth anxiety, depression, suicide, and accidental overdoses—including from synthetic opioids, namely fentanyl. I come up empty when trying to think of any cause more deserving of greater funding and committed focus than these. If the government were to better educate the public, discourse would shift to prioritize phenomena that carry the immediate and irreversible risk of death—a trait absent from the nicotine products so much alarm is sounded over.

Educate, not dictate

There is a fundamental premise that the United States was founded on the principles of individual liberty, and alongside other defined objectives, government bodies should fortify that foundational code rather than diminish it. For decades, the government has successfully focused on educating the public on the harms of smoking—an unmistakably unhealthy activity. And yet, despite total usage decreasing, there remain millions of adults who choose to smoke cigarettes and would like to continue to do so, no matter the health consequences. At the same time, there are also many who would like to quit, or at least reduce their usage. Regardless of where anyone rests on that spectrum, they are deserving of accurate data so that they can make their own informed decisions. This brings into question the FDA’s stated goal within its new strategic plan to Enhance Knowledge and Understanding of the Risks Associated With Tobacco Product Use. Its desired outcome is that the public receives health communication and education that is timely, clear, and evidence-based. This appears entirely reasonable—good decision-making as an output requires equally good input. But the administration’s more recent track record when it comes to appropriately educating the public on the nature of nicotine is poor, to put it mildly.

The newly unveiled strategic overhaul presented by the FDA is not the first. On July 27, 2017, the FDA announced a new comprehensive plan for tobacco and nicotine regulation (emphasis added):

The goal is to ensure that the FDA has the proper scientific and regulatory foundation to efficiently and effectively implement the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. To make certain that the FDA is striking an appropriate balance between regulation and encouraging development of innovative tobacco products that may be less dangerous than cigarettes, the agency is also providing targeted relief on some timelines described in the May 2016 final rule that extended the FDA’s authority to additional tobacco products.

Striking that appropriate balance never occurred—the environment we find ourselves in now, with an overwhelmed product review process and proliferating illicit disposables, is the direct result of the administration being completely unprepared. To add, last year, in an interview with the AP, Brian King stated:

I’m fully aware of the misperceptions that are out there and aren’t consistent with the known science. We do know that e-cigarettes — as a general class — have markedly less risk than a combustible cigarette product. That said, I think it’s very critical that we inform any communication campaigns using science and evidence. It has to be very carefully thought out to ensure that we’re maximizing impact and avoiding unintended consequences.

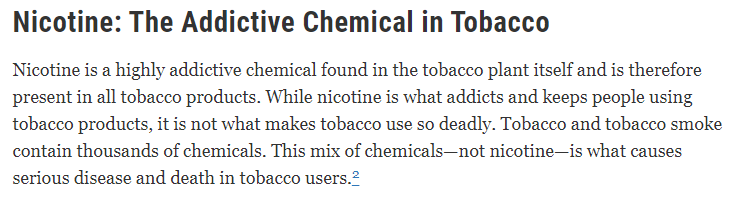

What has been achieved to educate the public on relative risks between product categories over the five years between the two above statements and in the year following? Very little. Studies show a staggeringly large percentage of the population believes vaping to be equally or more harmful than smoking cigarettes. Such types of misbeliefs even extend to medical professionals, with a disproportionate number (~80%) surveyed in a 2020 study believing that nicotine is carcinogenic. How do such misconceptions spread and how has the FDA failed to appropriately share the information that is clearly presented on its website?

There is a litany of similarly compelling statements made by prominent health organizations:

The accepted medical position is that nicotine itself… poses few health risks, except among certain vulnerable groups.

Use of nicotine alone, in the doses used by smokers, represents little if any hazard to the user.

New England Journal of Medicine:

Beyond its addictive properties, short-term or long-term exposure to nicotine in adults has not been established as dangerous.

The list goes on and on.

It is perplexing as to why the FDA has not pushed this front and center. Is the tiptoeing due to a fear that by educating adults on the nature of nicotine they might fully educate youth as well, leading to greater usage? The solution can not be to offer nothing. The government is merely keeping adults uninformed. Relative to all of the talk centered around Think of the children™, there is a seemingly absent interest in thinking about adults. Most smokers are adults, smoking is the most harmful of nicotine delivery methods, and most of that harm occurs over time with prolonged use. While many adult smokers will choose to continue to smoke, those who wish to quit or reduce their usage can clearly benefit by switching to other nicotine products that exist toward the lower end of the continuum of risk. The Medical University of South Carolina just completed and published a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of nicotine vaping as a smoking cessation method. Matthew Carpenter, Ph.D., first author of the study, stated:

It’s rarely the case that you’re proven correct for almost everything that you predicted.

Here, it was one effect after another: No matter how we looked at it, those who got the e-cigarette product demonstrated greater abstinence and reduced harm as compared to those who didn’t get it.

Such findings are undoubtedly appalling to groups such as the World Health Organization, who remain wholly opposed to all forms of nicotine usage and support prohibitionist policies. As we’ve seen before, prohibition does not work, and I’ve previously distilled related thoughts to the following:

If monarchs and dictators using the threat of death could not stop tobacco usage, what would make the progressive democracies and republics of today fair any better? Simply put, there is no way to put the genie back in the bottle. This is not to say that we should not regulate tobacco and nicotine or that all historical regulation has been right or wrong. Rather, it seems most practical to cheer for regulation that further thwarts underage access and usage of tobacco and nicotine while at the same time providing ample information, resources, and options for adult consumers to make informed choices.

Further, a statement from the UK’s Royal Society of Public Health is particularly thought-provoking:

Nicotine: no more harmful to health than caffeine.

Caffeine is the most widely consumed drug in the world. The vast majority of adults in the United States (~85%) consume caffeine daily. For many, this is compulsory behavior and, if not maintained, can lead to specific withdrawal effects. This is dependence. However, for most, at moderate intake levels, there is no risk or occurrence of serious net harm—no threatening addiction. Unfortunately, the terms dependence and addiction are often conflated. With this in mind, it is high time that a concerted effort be made to discern between the two within the discussion of tobacco and nicotine. If specific novel products within the categories of vapes, heated tobacco, and nicotine pouches are scientifically substantiated to allow informed adults to use nicotine without the risk of serious net harm, those products should be embraced rather than shunned by regulators. Other governmental bodies around the world have already assumed this idea of Tobacco Harm Reduction, such as the United Kingdom National Health Service, in which clear and concise language is offered with no ambiguity. Such unfettered pragmatism should trounce delusional idealism.

The FDA’s new plan is built upon the themes of science, health equity, stakeholder engagement, and transparency. With respect to all four, education must be at the forefront of the FDA’s efforts. The industry is evolving and while smoking continues to decrease, demand for novel products continues to grow. The stigma around nicotine must be shed, discourse must be untainted, policy must be formed around science, and although the FDA has earned tremendous skepticism regarding its ability to deliver, nothing would be better than being proven wrong.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

I own positions in British American Tobacco and other tobacco companies such as Altria, Philip Morris International, Imperial Brands, and Scandinavian Tobacco Group.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

h/t @Doomberg. The government’s approach to nicotine shares parallels with energy policy - a refusal to look at the fundamentals, no interest in respecting science, and no willingness to adopt any policy that embraces the idea that Better is Better.

Hi Devin, thanks for sharing your thoughts.

If you haven't read it already, I think you will find this article here interesting: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-e-cigarette-titan-behind-elf-bar-floods-us-with-illegal-vapes-2023-12-06/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email