“We are now the second-largest publicly-held cigarette company in the world and the third-largest brewer in the U.S.” - Joseph F. Cullman III, Philip Morris CEO, Presentation to New York analysts, 1976

When you are a wildly profitable company, you have a few ways to allocate your excess riches:

Reinvest into your business.

Buy other businesses.

Reduce your debt.

Return money to shareholders via dividends or share repurchases.

Throw the money into a woodchipper.

Sometimes 2 and 5 are hard to tell apart.

On Friday, Altria announced exchanging its minority stake in JUUL for a license to certain heated tobacco intellectual property from JUUL. The commentary surrounding the deal has been disproportionally alarmist; no doubt a visceral reaction, quickly pointing to the still-healing wounds left by the company’s less-than-stellar capital allocation decisions of the past. Pair this with the spreading rumors of Altria’s interest in acquiring vaping company NJOY Holdings, and you have yourself a good old-fashioned panic.

The reactions aren’t entirely unwarranted, but they may be over the top. While Altria’s investment history isn’t flawless, as a whole, it isn’t anywhere near as bad as you might think.

Let’s revisit how we got here.

In 1976, Philip Morris looked unstoppable. The company commanded an impressive 25% share of the U.S. cigarette market, a 5% share of the international market, and held nearly 12% of the U.S. beer market thanks to having purchased the Miller Brewing Company 7 years earlier. In that timeframe, revenues, net income, and earnings per share had nearly tripled. The period’s optimism is perfectly preserved in the archived piece below:

But as operations continued to hum along, the company found itself in a conundrum. The tide of the domestic market was turning, with health, litigation, and regulatory concerns mounting. Seeing the success of the Miller Brewing acquisition, Philip Morris decided to further diversify, and in 1985 completed its acquisition of the General Foods Corp for a staggering $5.6 billion, including the assumption of ~$4 billion in debt. Roger Spencer, an analyst with PaineWebber in Chicago at the time, was quoted in The Chicago Tribune:

“Down deep, Philip Morris knows that the tobacco business is going down.”

“Chances are that, in five years, you’re going to be making more in food than you are now, whereas in tobacco, you know that is going down.”

CEO Joseph F. Cullman III retired two years later, leaving behind an exceptional legacy, including the success of the Marlboro Man campaign, turning the company’s flagship brand into a nearly incomparable cash machine - flowing riches future management would continue to diversify with. In 1988, Philip Morris paid a whopping $13.1 billion in cash to acquire Kraft Foods, Inc, and the following year merged General Foods Corp into it to create Kraft General Foods.

Then things took an ugly turn.

There was Marlboro Friday in 1993 when shares of Philip Morris fell by 26% in a single day. 5 years after that was the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, which was hailed as the end of Big Tobacco. But Philip Morris kept moving forward, and in 2000, paid an eye-popping $18.9 billion, including the assumption of $4 billion in debt, for Nabisco, from rival tobacco company R.J. Reynolds. A year later, Philip Morris IPO’d a partial stake in Kraft. Another year went by, and then Miller Brewing merged with South African Breweries (SAB) to form SABMiller. With SAB assuming ~$2 billion of debt as well as providing Miller with additional equity, Philip Morris found itself with a 36% stake in the new company.

Philip Morris rebranded to Altria the following year.

But even with the new name, Altria was the old, stuffy company that people loved to hate. The company foolishly divested its foods division Kraft in 2007 and then spun off its international tobacco division, Philip Morris International, in 2008. Just a year later, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act was passed, further crushing Altria’s autonomy and leaving it all out of tricks. Or at least that’s how so many people spin the tale.

Backing up to December 2007, right in between the Kraft and PMI spins, Altria acquired cigar company John Middleton. While some analysts applauded the deal, it received plenty of criticism, with those against arguing that the $2.9 billion sticker price, paid in cash, should have been paid out to shareholders instead.

What was Altria buying? For the full-year 2007, John Middleton was expected to generate $360m in sales and $182m in operating income. The price paid equates to about x16 EBIT. Perhaps reasonable for an absurdly high-margin business that for the previous 4 years grew revenues and operating income at CAGRs of 10% and 13%, respectively. However, that’s still not the whole picture. The terms of the transaction also gave Altria $700 million in present-value tax benefits. Subtracting that out nets a purchase price of $2.2 billion, or x12 EBIT.

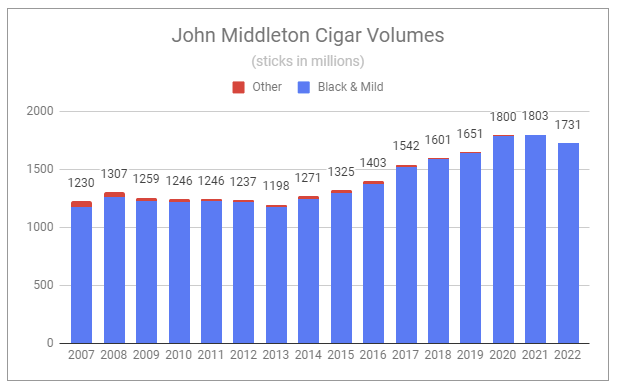

While cigarette volumes continued to decline, Middleton cigar volume remained near-stagnant for half a decade and then began to grow:

Critically, along with holding a >30% share of the machine-made cigar market, Altria increased prices on cigar products every single year. Here are just the last several years disclosed:

Mind you, the machine-made cigars already had absurdly high margins which were also understated as the revenue figure cited includes excise taxes billed to customers. On top of this, there has been minimal reinvestment need, and the operations are outrageously capital-light - as per the terms:

Assets purchased in the Middleton acquisition consist primarily of non-amortizable intangible assets related to acquired brands of $2.6 billion, amortizable intangible assets of $0.1 billion, goodwill of $0.1 billion and other assets of $0.1 billion, partially offset by accrued liabilities assumed in the acquisition.

The exact contribution of cigars to operating income is not disclosed by Altria and is instead consolidated into Smokeable Products along with cigarettes. Nonetheless, with rough math, associated operating income has increased several times over, and it’s hard to conclude anything other than this was a wonderful deal made.

In 2009, 2 years after acquiring JMC, and a mere 5 months before the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act was passed, Altria acquired UST Inc by offering UST shareholders $69.50/share; a 28.9% premium to the previous closing price. The deal had a mix of financing, including an initially committed $7 billion bridge courtesy of Goldman Sachs & Co. and J. P. Morgan, and with the assumption of ~$1.3 billion of debt and $600 million in integration-related charges to be expensed over time, the total transaction was valued at approximately $11.7 billion - more than x5 the net cost of the John Middleton deal. UST, the largest smokeless tobacco company in the U.S., reported 2007 net sales of $1.95 billion, operating income of $853 million, and net income of $520 million, putting the deal at around x13.7 EBIT. (UST’s 2007 10-k is a fun throwback to read through if you are curious.)

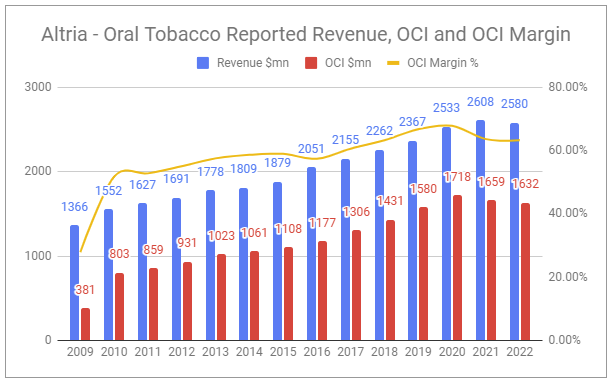

Once again, many were critical of this deal, disappointed that Altria had reduced its share repurchase authorization for the next 3 years by nearly half in order to finance it. And again, this failed to capture the full picture. Altria expected to realize significant synergies, to the tune of $250 million, by eliminating redundant expenses, as well as leveraging its existing infrastructure and distribution to drive sales growth. And it did:

Following the deal, oral tobacco product volumes modestly grew, and Altria once again continued to exercise pricing power every single year. Here are just the last few:

Steadily increasing prices on top of growing volumes led to a rather predictable expansion of margins and related operating income:

And yet even that excludes a key detail. UST owned Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, which Altria also received in the transaction. Despite lock-step growth for a decade, the wine industry saw a massive inventory glut in 2019, which was especially damning for Ste. Michelle, who had continued to aggressively reinvest. Prior to the acquisition, Ste. Michelle accounted for >1/3 of UST’s Capex, but a negligible component of operating income. And then, in 2020, COVID struck. To say it had a pronounced impact on the business would be an understatement:

Altria decided to tap out of the wine game to focus on tobacco and nicotine, and on October 1, 2021, completed the sale of the Ste. Michelle Wine Estates business for $1.2 billion - approximately 10% of the purchase price of UST. Discounting back the sale price to the acquisition date using Altria’s long-term WACC gives a value of ~$500 million. Factoring that value, additional integration-related costs, and recognized synergies obtains an adjusted EV/EBIT ratio for the initial acquisition to around x12, approximately what was paid for JMC.

Looking again, you may notice a distinct leveling in revenues and operating income for the oral tobacco segment in 2021-2022. The segment unit volumes chart highlights the root cause: on!.

on!, Altria’s tobacco-free nicotine pouch, was commercialized after forming the subsidiary Helix Innovations after taking an 80% stake in Swiss company Burger Söhne for $372 million in 2019 (Altria acquired the remaining 20% stake in 2021 for $250 million). In an attempt to gain market share in the rapidly growing modern oral segment, Altria has been aggressively promoting on! and using discounted pricing to spur purchases. With formidable competition, namely Zyn (with new ownership), the price/mix headwind, while lessening, is likely to persist. Yet, even while subsidizing new product growth, the oral segment actually carries higher margins than smokeable products for Altria.

All of this gets completely masked by other recent deals. People correctly criticize Altria’s 2019 $1.8 billion investment for 45% of Canadian cannabis company Cronos, which has been continually marked down over time. Cronos has been very good at incinerating money and committing fraud. But even greater criticism is focused on one of the most obscenely overpriced deals in history. In 2018, Altria paid $12.8 billion for a 35% stake in JUUL, 4 years after paying $110 million for e-cig company Green Smoke. I’ve long been critical of the JUUL deal and have continually valued the stake at $0. While there has been the lingering possibility of Altria buying the remaining 65%, it severing the non-compete should have been a clear signal. Is there any way the recent announcement to exchange the 35% stake for a non-exclusive, irrevocable license of JUUL’s heated tobacco IP makes sense? Would it not make more sense to wait to see how the legal process plays out post-MDO? I think there’s a better question: At this point, is anything regarding JUUL a material concern? With Altria having marked down its stake to $250 million, the JUUL stake represented less than one quarter of one percent of Altria’s enterprise value. I can’t imagine that weighed heavily into anyone’s view of Altria’s core operations. Though, you could argue that such massively botched capital allocation decisions, especially more recently, raise a red flag on management, leading you to steer clear of the company. That’s not unreasonable, and Cronos and JUUL are two prime examples of the greatest risk facing the tobacco industry:

For more than half a century, tobacco companies have been keenly aware of the existential peril presented by declining volumes in their core business. But, as history has shown, the greatest risk to these companies is not the threat itself but rather how they attempt to overcome that threat. From Altria overpaying for stakes in JUUL and Cronos, British American Tobacco’s fervent diversification in the 1960s, to the theft-like actions at RJR Nabisco and the subsequent LBO, tobacco companies are experts at self-sabotage. You could argue that this is overly critical, as there have also been wonderfully accretive investments made by tobacco firms. Nonetheless, the risk remains. Any great business can become a terrible investment if management dreams big enough and has the willpower to follow through on a few half-baked ideas.

It’s wild to consider that the net total price for Altria’s JUUL and Cronos investments was ~$14.6 billion, while the net total price for John Middleton Company, UST, and on! was nearly identical, at ~$14.5 billion. The former 2 will likely leave little to show, but the latter 3 will likely produce substantial cash flows well into the future. To add, in 2016, Altria’s 36% stake in SABMiller turned into ~10% of Anheuser-Busch InBev, by far the largest beer brewer in the world. Altria’s shares are now priced at over $12.2 billion, an x94 increase over the initial $130 million purchase price of Miller Brewing. That’s made even more impressive by the fact that the figure excludes various earnings and dividends produced over the last half-century.

Regarding the newest of deals, it’s hard to say what will come of Altria’s IP attained from Poda, a deal seemingly forgotten. Altria exchanging its JUUL stake highlights the company’s interest in finding other, less tenuous routes to position itself in the vaping segment, such as by acquiring NJOY for the rumored $2.75 billion, plus a potential $500 million earn-out. A deal like that would likely necessitate Altria divesting its JUUL stake anyways due to antitrust concerns. I would anticipate more details from Altria’s Investor Day later this month, when we can also expect two new product announcements.

It’s easy to look through the lens of hindsight and criticize any particular deal. It’s even easier when you can pretend you’d allocate that same capital to other deals, or perfectly timed share repurchases. But ultimately, many acquisitions within the industry have actually been far better than they look - those labeled good and bad alike. With regulation preventing new competition, many transactions further concentrate control, reinforcing the position of incumbent brands, and allowing them to continue exercising incredible pricing power. Is Altria’s track record perfect? No. But even the company’s mistakes highlight the strength of the underlying business. How many companies exist that could afford such missteps? Very few.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

I own positions in Altria and other tobacco companies such as British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Tags: MO 0.00%↑ PM 0.00%↑ BTI 0.00%↑ BUD 0.00%↑ KHC 0.00%↑ CRON 0.00%↑

Do you expect the latest deal to allow MO to monetize the deferred tax asset associated with JUUL?

Excellent piece. Thanks, Devin.