“I intend to live forever, or die trying.” - Groucho Marx

The Dutch East India Company was born at the turn of the 17th century. Officially named Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC for short), it was an absolute behemoth that united small trade companies, expanded bases into Sri Lanka, India, and Indonesia, and held an effective monopoly on commerce between East Asia and Europe. It domineered over its expansive empire with a huge navy and its own private military - some of the largest in the world at the time. It even issued its own coins. One sits on my office bookshelf:

The VOC’s financial innovations extended far beyond issuing its own coins. It was the first multinational corporation and the first publicly-traded company which was listed on what would become the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. Any Dutch resident could purchase shares in the company, and shares also traded on secondary markets. Who wouldn’t want to own a piece of the most powerful and profitable company in the world? From inception, shares in the company paid substantial annualized dividends in currency and occasionally in rare and valuable spices.

The VOC also amplified the Dutch Golden Age. The Netherlands, whose lead in trade and military was the envy of all of Europe, saw an exploding interest in science and art. It was during that period that the first recorded financial bubble occurred: Tulip Mania. The peak of the speculative frenzy, February 1637, saw certain rare bulbs fetch prices over 10 times the annual income of a skilled craftsman. Yet, despite being the most famous of bubbles, it was short-lived, and its collapse was nowhere near as disastrous as most are led to believe.

During that same period was a separate occurrence much more important than Tulip Mania, yet oddly receives very little coverage:

Bearer bonds.

The fast-growing economy of the Netherlands attracted huge numbers of immigrants, accelerating the need for infrastructure. Windmills and peat were leveraged for cheap and abundant energy, and canals and waterways made transport easy. To finance these projects, numerous levels of government began to issue bearer bonds. The term ‘bearer’ connotates the fact that the bearer (owner) must present the physical bond in order to receive payment.

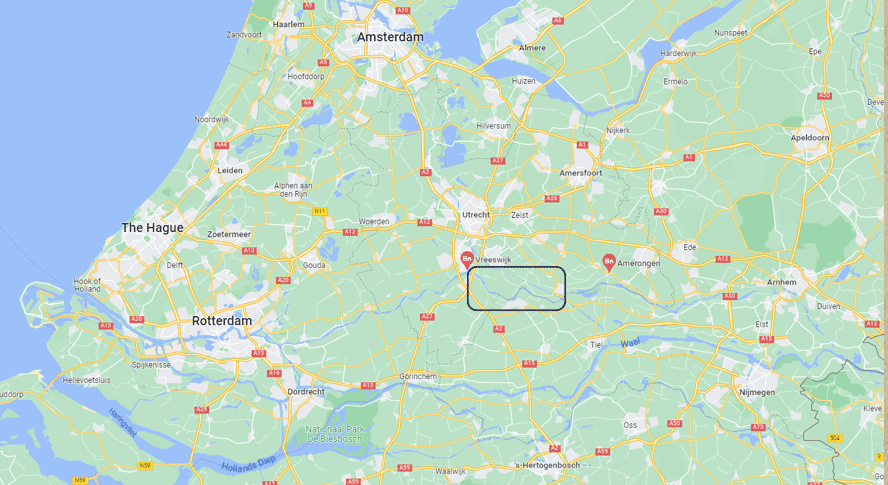

In 1624, to control the flow of water and prevent flooding, a local water authority, Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams (NLD), began to issue bearer bonds to raise funds to repair dykes along the Lek River.

The annual interest payment of 2.5% was quite agreeable to the government. More than half of the local lands were susceptible to flooding, and without the dykes, the economic damage would be much more severe. What’s most interesting, however, is that, unlike modern bonds, these bearer bonds have no maturity - there is no stated date on which the principal is to be repaid, and thus, they will pay annual interest in perpetuity. Granted, the bonds were initially denominated in Dutch Guilders, and accounting for inflation and a switch to Euro, the annual payout is rather measly.

In 2003, Yale University acquired such a water bond, initially issued in 1648, for the lofty price of €24,000. Upon purchase, it was discovered the bond had not paid interest for 12 years. Remedying that error, Yale received a whopping €136.20. With such a paltry annual interest payment, the school will never get rich from it. But that was never the goal. It sits as an artifact in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

What a marvel: a 374-year-old bond, still alive and paying interest.

This is in stark contrast to the equity shares of the VOC. For over 100 years, the company paid dividends to its shareholders. It looked to be a sure-fire investment likely to produce an endless stream of income tied to global trade. However, as the company continued to grow, so did the corruption within, and debt-financed growth was shackled by smuggling, ballooning costs, and competition from other European nations. The Indian assets of the VOC were nationalized by the British crown in 1858, and in 1874, as a mere shadow of its former self, the company was finally dissolved.

A bond issued by a small water municipality outlived the largest, most powerful company on the planet. It seems impossible, yet it happened. This raises an interesting question:

If you were an investor sometime during the 17th-19th centuries, how would you evaluate NLD water bonds and VOC equity?

From a valuation perspective, the water bond would have been much easier to tackle. As a perpetual, you could simply divide the anticipated payment by your desired hurdle rate, and since payments are fixed, there is no growth to account for. Your hurdle rate, naturally, would extend beyond your required rate of return and include risks such as the chance of default or concern around the currency it was denominated in. If the bond were to pay 5 and your hurdle rate was 10%, the fair value would be 50. If you could insure against those additional risks for say, 2% per annum, your hurdle rate would be 12%, lowering the fair value to 41.66. And naturally, as an astute investor, you wouldn’t want to pay fair value - you’d want to get a steal of a deal. So perhaps you’d sit patiently until the bond was priced at 30-35. However, if the bond pays 5 nominal and a 2.5% yield, the price would be 200. The bond would have to fall more than 80% to get into your target purchase range. Perhaps the only thing that would cause such a drop is a risk you failed to calculate, and you’d never want to buy it then anyways!

The VOC shares are an entirely different story. You could assess the Dutch East India Company at the enterprise level. Looking at operations, you’d evaluate the supply and demand of each rare good held and all of the associated costs to move them. You’d take a look at the company-issued bonds to see how well the interest payments were covered and just how much debt there was. There’d be the concern of the company issuing more shares, diluting the existing equity. But don’t forget, this company is gargantuan compared to all others and even has its own military! And like so many others at the time, you’d likely extrapolate growing cargo volumes well into the future. Perhaps that would be your rationale for paying a lofty price to get in on the action. And even if you did pay a bit of a premium, and had you invested at some point in the first 100 years, you’d likely have made a fortune. But by reinvesting all of those dividends back into the company, eventually, you or your heirs would be left with nothing.

All of this is to say: investing is hard. What seems intuitive or obvious can often be wrong, and we should always question ourselves when we feel completely confident in our abilities. For many, it’s tempting to continually extend one’s time horizon and exercise patience to generate outsized returns off of the market’s mismatches between duration and expectations. But how far is too far? The line is out there somewhere.

Forever is a myth.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment here or message me on Twitter.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

I love this! US common law has a rule against perpetuities, but of course some still exist like certain conservation easements. There is also the question of how long forever is? 99 year ground leases, or 100 year bonds issues by some colleges seem to accomplish something akin to a perpetuity. By far though the most interesting is the structure of SPY which "will cease to be on Jan. 22, 2118, or 20 years “after the death of the last survivor of the eleven persons” https://www.thinkadvisor.com/2019/08/12/meet-the-spy-11-kids-with-250b-riding-on-their-lives/

VOC is much like US today as it has a near monopoly on currency and military power. I can't predict when a cycle will end as different each time. To overcome this I think insurance with a small % in bearer assets is good insurance. It is greedy of me not to get some insurance. This safety blanket allows me to invest so even if my duration and expectations are totally wrong I will survive.