“The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help.” - President Ronald Reagan

The United Kingdom is moving forward with its generational smoking ban. The proposal, formerly known as the Tobacco and Vapes Bill, cleared its first major hurdle this past Tuesday, with MPs in the House of Commons voting 383 for and 67 against. The House of Lords is anticipated to vote on the bill’s final approval in June.

“Historic.”

“Monumental.”

“The single biggest preventative health policy in a generation.”

The intent of the bill is to shield younger generations from addiction, saving thousands of lives and billions of dollars in associated costs. Proponents of the measure have already begun performing cartwheels in celebration. However, enthusiasm for the Tobacco and Vapes Bill should be curbed, and a high degree of skepticism toward its ability to deliver on its goals should remain firmly in place.

The Tobacco and Vapes Bill at its core

In July 2019, the UK government announced its aspirational goal of a smoke-free 2030. The goal was not to be truly smoke-free but rather to be smoke-free in the sense set forth by the World Health Organization, which defines it as an adult smoking prevalence of below 5%. The government has now conceded that previous efforts will fall short, and the goal will not be met if no radical efforts are taken.

The Tobacco and Vapes Bill would prohibit the sale in England and Wales of all tobacco products, cigarette papers, and herbal smoking products to those born on or after January 1, 2009. It would also mark purchasing such products on behalf of anyone born on or after January 1, 2009, as an offense. This is rationalized by the following train of thought:

Youth (under the age of 18) are unable to make sensible decisions.

Most smokers initiate smoking at a young age.

By prohibiting younger generations from ever being able to legally acquire tobacco products, usage prevalence amongst those groups will be non-existent, and total usage prevalence will steadily decline toward zero.

To be clear, this bill does not do much at all to prevent underage smoking. Within the jurisdiction concerned, the legal age to purchase tobacco products is already 18. What this bill is doing is setting a new precedent in which adults, rightly able to make all other decisions concerning their own lives, will never be able to decide for themselves whether to smoke or not to smoke. A government that has historically championed individual liberty for its people is stripping specific members of society of their ability to choose, creating a multi-tiered class system in the process. Those who happen to turn the magical age of 18 on or after January 1, 2027, will never have the right to make the choice for themselves as to whether or not to smoke. They will never have the ability to make that adult choice, whether they are 18, 25, 40, 50, or 90 years old. Those who turn 18 at any time prior to that date will enjoy the same freedom all other adults in the country currently exercise.

The stripping of individual liberty is defended by the argument that younger age groups can not make sensible decisions for themselves. That was certainly used to rationalize increasing the legal age of sale of tobacco from 16 to 18 in October 2007, following which there was certainly a reduction of smoking instigation amongst those under 18. Should you believe that all demand vanishes when a specific portion of the adult population is barred from purchasing a product that is readily available for the rest? No. No. To answer the question of what a society would look like with a generational smoking ban in place, it would be useful to look at precedents set by other countries that have enacted similar measures. But the only country that has attempted a generational smoking ban is New Zealand, which repealed its generational smoking ban earlier this year, long before its effects could be felt. In fact, there are only two instances in recent history in which the prohibition of tobacco was attempted. One is South Africa, in 2020, which I highlighted previously:

Proponents of making cigarettes or nicotine illegal would best be served to study the 1920-1933 period of alcohol prohibition in the United States, or more recently, 2020 in South Africa, in which tobacco sales were banned during the COVID-19 lockdown, largely funneling sales to illicit sources and creating a windfall for the country’s black market.

The second example of tobacco prohibition is Bhutan, which enacted legislation in 2004 that prohibited the manufacturing and sale of tobacco products within the country. However, certain amounts of imported products were allowed, which faced heavy duties and taxes. This policy was ultimately reversed during the pandemic. What occurred during prohibition? A black market boomed, profiting from filling the void in the market to meet demand, and underage cigarette usage prevalence grew steadily.

It is reasonable to expect the continued growth of a black market as a natural result of the UK passing its generational smoking ban. Already, large quantities of cigarettes are smuggled in to skirt the exorbitant taxes placed on the product, with the illicit market in tobacco duty and related VAT estimated to have been £2.8 billion from 2021 to 2022. Likewise, hand-rolling one’s own cigarettes remains popular due to the lofty prices of traditionally manufactured cigarette brands, and approximately one-third of all rolling tobacco in the country is sold illegally. Black markets hit governments with a double whammy: They reduce recognized excise tax proceeds while forcing the redirection of other resources to tackle growing illegal activity.

In a similar vein, the rate of compliance at the retail and social levels must be questioned. Rather than eyeing down a customer and ballparking their age to be above 18 with a comfortable margin of safety, as is often currently done, retailers will need to formally verify the purchaser’s age. Otherwise, they face the threat of new spot fines for underage sales. How many will actually do this? Perhaps instead, each year, they will merely perform a glancing check to estimate a purchaser's age to be 19, 20, 21, 22, and so on. Further out, there will be even more questionable periods. For example, decades from now, there will be a specific moment when 53/54/55-year-olds are prohibited from purchasing while 56/57/58-year-olds can do so, but far fewer of any of those ages will be carded because, at a glance, they will all look ‘about right.’ Not to mention, while to be made explicitly illegal, those older than the cutoff date will assuredly be happy to purchase and share with their marginally younger friends. That is, after all, what friends do.

Enforcing bodies, such as trading standards officers, have already stated that the court proceedings against offending retailers within the current regulatory framework are time-consuming and further limit their operational capabilities. To handle these concerns, the new bill has marked to provide £30 million in additional funding per year for the next five years for enforcement. Surely, such funding would prove to be a material shortfall when considering the problematic environment this new bill would foster. After all, laws in place that are not complied with or adequately enforced are practically indistinguishable from having no law at all. This is most perplexing when considering the monumental cost savings that continue to be a focal point of proponents.

The missing math

Common battle cries chanted by proponents of tobacco prohibition include lyrics condemning the exorbitant tobacco-related costs that stunt societies that would otherwise be more prosperous. Various studies have been conducted to estimate the total costs associated with tobacco usage, and the UK figures are rather staggering. When Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the generational smoke ban, he stated (emphasis added):

I want to create the first smoke-free generation. Most smokers take up cigarettes when they’re young. Millions desperately want to quit, but find it hard because it’s so addictive. But if we can break that cycle and stop the start, we’d be on our way to ending the biggest cause of preventable death and disease in our country and build a brighter future for our children. So we will change the law to ensure children turning 14 or younger this year can never legally be sold cigarettes in their lifetime. This means the age of sale will increase by one year each year, which will prevent future generations from ever taking it up. Smoking kills. It’s as simple as that. And if we don’t act, half a million more people will die from smoking by 2030. It also places huge pressures on the NHS and costs our country £17 billion a year.

£17 billion in annualized costs have been weighed against the receipts of government income from the taxation of tobacco products, which most recently measured £10 billion (suggesting a shortfall of £7 billion, if you don’t have a calculator handy.) However, there are some serious caveats here. Within the bill, the £17 billion in annualized costs cited include £1.9 billion in yearly NHS costs from smoking-related hospital admissions and primary care treatment costs and £1.1 billion in yearly costs to local authorities in England on care for smoke-related illnesses later in life. The vast majority of the total costs, £14 billion, are attributed as a cost to productivity. This cost to productivity should not be weighed against tax receipts because it is not a direct cost to the government but to the individuals—comprised primarily of the estimated impact of job losses, reduction in wages, and working for fewer years due to smoking-related illnesses. Further, what should be stressed is that this type of math shouldn’t be a primary focal point for or against the bill because it is incomplete, and the modeling for the smoke-free generation policy explicitly states critical missing components:

The model does not include the costs incurred in remaining alive longer. This is standard practice for health economic analysis. In line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance491, we have not included costs unrelated to the conditions of interest. However, it is true that there will be additional costs for people who live longer, even excluding government payments like pensions that represent a transfer between parties and do not constitute a societal cost. We have not estimated the extent of these costs here. People who live longer will also contribute to society, and this is not captured beyond direct productivity impacts either.

And yet, there remains the most incomplete aspect of the model when considering potential impact…

An incomplete model

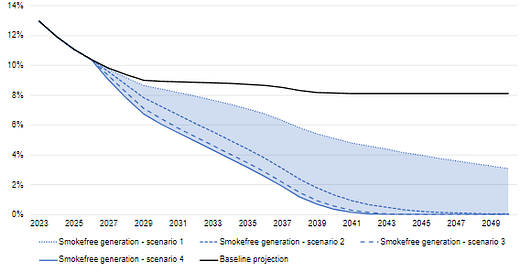

The UK government’s modeling for the smoke-free generation policy utilized a handy dandy Markov chain. Through the miracle that is advanced stats, this approach provided the baseline and forecast prevalence charts cited earlier and provides much of the basis for rationalizing the bill. As wonderfully illustrative as the Markov model is, it includes certain assumptions and simplifications, so there are limitations to understanding the potentially likely consequences of the smoke-free generation policy. The publication directly acknowledges this and provides both potentials for underestimation and overestimation alike.

Potential underestimation

Some elements of the model likely underestimate the impacts. For example:

we assumed that former smokers who quit 10 or more years ago have the same risk profile as non-smokers and the model only applies per person risk and cost figures based on former smokers in general to those who quit more recently

the model assumed the policy only impacted on instigation rates rather than any further effects like people smoking less

the model calculated health outcomes only in terms of mortality and the onset of some smoking-related diseases - this includes QALY calculations that refer only to mortality effects, so do not include the considerable quality of life impacts of smoking-related morbidity

The truncation of risk profiles nearly assures errors that may be compounded by other factors. Similarly, the model focuses on instigation while the effect of smokers smoking less over time goes unchecked. The average number of cigarettes consumed per day by British smokers has steadily declined for decades, with male consumption falling from an average of 21.6 sticks per day in 1979 to 9.2 sticks in 2019. Female smokers’ average sticks per day fell from 16.6 to 9.0 over the same period. There are two implications should this trend continue. First, all else equal, the total impact (beyond instigation) of the Tobacco and Vapes Bill would be greater in absolute terms while lesser relative to the baseline model. Secondly, this hints at what is likely to be a primary driver of overestimation, which is further highlighted in the reported potential overestimations.

Potential overestimation

On the other hand, the model may overestimate effects in some areas. It does not consider the effects of smoking policies on vaping, so does not including potential detrimental health effects of increased vaping (although neither does it consider the effects of vaping-related government policy). It also relies on ASH estimates on the cost of smoking. These estimates are the best available that we know, but they may potentially overstate the effect of smoking on employment and earnings as well as the effect on social care. They also do not include all quantifiable costs of smoking, which would offset this to some extent.

So, for example, their productivity loss regression analysis controls for age, ethnicity and education, but does not control for all aspects of deprivation, which is correlated with higher smoking rates. It is possible that some factors related to deprivation may result in both reduced earnings and higher smoking rates, but those reduced earnings are not due to smoking.

Also, we applied societal costs of smoking per person to the whole modelled population of current smokers and former smokers (who quit up to 10 years ago). So, we modelled these to accrue earlier in life than when they might occur in reality, given these costs predominantly arise in older age.

The UK government has repeatedly acknowledged that vaping, while not entirely safe, is markedly lower risk relative to smoking cigarettes. With certainty, trends in average cigarette consumption rates have been aided in recent years by smokers becoming poly-users, replacing a portion of their cigarette consumption with vaping. Similarly, comprehensive analysis shows that vaping provides an effective offramp for smokers looking to quit, and former smokers who exclusively vape have a lower propensity to relapse back to cigarette smoking. These facts reinforce the notion that Tobacco Harm Reduction policies should embrace next-gen products, including vaping, to achieve maximally effective results. Yet, while other legislation, such as The UK’s ‘swap to stop’ scheme, might improve adult accessibility to reduced-risk vapes, the Tobacco and Vapes Bill would apply more stringent regulations around vapes on a category level, potentially limiting the appeal of such products to adults. Restrictions and regulations include limiting the flavors of products, packaging, product presentation, and point-of-sale displays. Further, under the guise of environmental considerations, the UK government has stated its intent to ban the sale and supply of disposable vapes. With disposable variants having become widely popular, there is a potential for the ban to be enacted before the generational smoking ban takes effect, partially eliminating an effective offramp and pushing more aggregate volumes into illicit channels.

The bill’s restrictions and regulations on vaping products also extend to other nicotine products, including nicotine pouches. However, the scope of the bill’s impact only explores nicotine and non-nicotine vapes and does not factor in the effect on other nicotine products. Haypp Group’s Nicotine Pouch Report for the UK, 2023, shows that 57% of pouch users began using pouches as a way to quit smoking. It also highlights that flavors play a critical role, with all consumer age groups having a flavor preference. As with vaping, restrictions to nicotine pouches will likely reduce the product’s attractiveness to adults, limiting switching, and will potentially push volumes into illicit channels, while current pouch users would be bound to experience a higher likelihood of relapsing back to smoking.

The most likely outcome

The fundamentally problematic issue of restricting adults’ autonomy suggests The UK’s generational smoking ban will be met with a low compliance rate and less effective enforcement than necessary to reach its goals, all while fueling the black market. By failing to fully embrace the harm reduction utility of reduced-risk products and potentially limiting their continued impact through additional legislation, the Tobacco and Vapes Bill will likely generate far more problems than it solves. Should it become law, I will be revisiting its effects many years down the line to see how wrong everyone was, myself included.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share. To further show your support, consider pledging a paid subscription to Invariant.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

I own positions in tobacco companies such as Altria, Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Scandinavian Tobacco Group, and Imperial Brands. I also own positions in Haypp Group, a major online retailer of reduced-risk nicotine products.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Resources:

The Tobacco and Vapes Bill, Impact assessment. Source

The Khan review, Making smoking obsolete. Source

UK Gov Modelling for the smokefree generation policy. Source

WHO Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), Bhutan 2019. Source

ASH Ready Reckoner. Source

UK Gov National Statistics, Historical Tobacco Duty rates. Source

UK Gov Official Statistics, Tax Gaps: Excise. Source

UK Gov Stubbing out the problem: A new strategy to tackle illicit tobacco. Source

Use of e-cigarettes among young people in Great Britain. Source

ASH Use of e-cigarettes among adults in Great Britain. Source

UK Gov Adult smoking habits in Great Britain. Source

ASH Smoking Statistics Fact Sheet. Source

Haypp Group The Nicotine Pouch Report 2023. Source

Cancer Research UK. Smoking prevalence projections for England. Source

Changes in smoking prevalence in 16-17-year-old versus older adults following a rise in legal age of sale: findings from an English population study. Source

Effect of unguided e-cigarette provision on uptake, use, and smoking cessation among adults who smoke in the USA. Source

You write, "After all, laws in place that are not complied with or adequately enforced are practically indistinguishable from having no law at all." I would have said that not only are they indistinguishable, but are in fact worse than having no law when the law abrogates an individual right or liberty.

Further, the creation of two classes of citizens, one class with a specific right and one without that right, whatever the right might be, should be morally offensive to any human. But I guess if the topic is public health, people and politicians will make exceptions.

But who knows? To paraphrase Tobias Fünke, it might work out for the UK (https://bit.ly/3xHLjLz).

Ronald Reagan’s very insightful quote in the beginning of the article thoughtfully applies to virtually any big government intervention to “protect” individuals from themselves & their individual choices.

I’m assuming the totally unregulated cigarette & vaping black markets are looking forward to a huge windfall if/when the UK’s generational smoking (& vaping) ban is enacted. What’s next for the UK? Banning alcohol like beer, stout, gin? Good luck. We all know how the USA’s prohibition on alcohol worked out back in the early 1900s. My guess is the UK will be in line for a similar result.