“Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” - Andy Warhol

There are few questions in finance more pressing than how to best value an asset. You could estimate a relative valuation; comparing it to something else. If asset A seems essentially identical to asset B, asset B is trading at X price, and asset A is trading at half of X, you might view A as cheap and buy it. You can make a lot of money this way. Do it enough times, and you’ll learn this is also a good way to lose lots of money. Maybe A wasn’t cheap. Maybe it turns out that asset B was expensive—perhaps both were actually only worth a quarter of X.

Another approach would be estimating an intrinsic value; the present value of all future cash flows. If you find an asset you believe can generate and return substantial cash each year for a few decades and you can buy it right now for a low multiple of those annual cash flows, you might really like that idea. You’d weigh the potential returns against opportunity cost - a hurdle rate - and maybe you’d go ahead and buy that asset if you don’t see any better prospects. This appears more sensible. But what if you’re wrong in your calculations? Maybe the asset only generates a fraction of that cash each year, or maybe it generates the full annualized amount but only for a few years before it magically disappears—that happens sometimes.

The real puzzle is that both of these approaches, although seemingly different, are much more related than given credit. To avoid major pitfalls, the first approach requires some type of anchoring to intrinsic worth; approach two. But, one way or another, approach two requires all kinds of relative comparisons; approach one. To point to just one of many variables, are you calculating a discount rate using an academic method, your personal hurdle rate, the current risk-free rate, a historical average rate, or some novel approach? Now apply such liberty to all of your other inputs.

This circular conundrum can get awfully complicated, and at times, it can feel like the only appropriate route is to break things down into more digestible bits by doing a sum-of-the-parts valuation. Perhaps, by using approach one or two, you’ve found a business that is dramatically undervalued because its components don’t seem to be fully appreciated by the market as a collective whole. Business C is priced at 5 and is made of parts D, E, and F, and you’ve calculated part D is worth 3, part E is worth 2, and F is worth 4. You buy shares of this business because there looks to be massive upside.

There are reasonable arguments to be made for this approach. You can bring the attention of a significant price/value mismatch to management, or maybe another smart investor has done that already, or maybe management identifies the mismatch themselves. Then they can sell off some assets to a buyer who is eager to pay a price more closely resembling full value. Or maybe they do a spinoff—unchaining an entire operating segment, allowing it to embark as its own corporate entity. That freeing experience can lead to a rocky adjustment period, but there are good reasons supporting that action’s fruitfulness. A former parent company and its spinoff can each refocus on their respective operations, avoiding the difficult act of juggling resources between. Each will become more of a pure play, potentially allowing greater transparency, and allowing both to become more attractive to investors seeking exposure to one set of business activities but not the other. Critically, the former parent and the spinoff can also optimize their capital structures to be more appropriate for their respective operations. When all of this is done well, a tremendous amount of value is unlocked.

But things don’t always go well. Sometimes you or the company have grossly miscalculated. Other times, no matter what price/value disconnect exists, and despite lacking well-reasoned justification, management has no interest in unloading assets or engaging in spinoffs. Without material activism or other external forces acting as a catalyst, you just end up sitting on your purchase for years as you watch the perceived discount persist. That can be a good reminder regarding true opportunity cost.

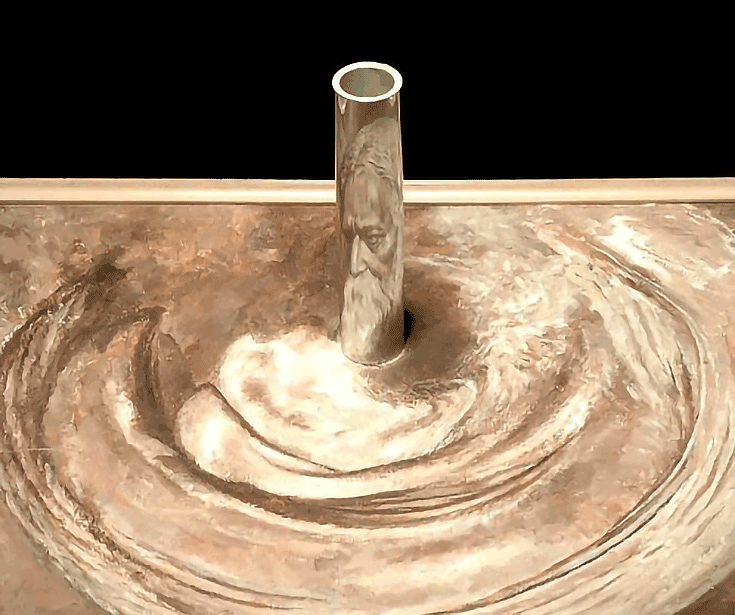

Something commonplace, and arguably more nefarious, is using a sum-of-the-parts approach to valuing businesses whose components can’t be separated without consequence—wholes worth more than their sums. I unexpectedly came across the most perfect illustration of this earlier in the year, when regenerative agriculturist Sam Knowlton wrote on polyculture overyielding:

A polyculture of wheat grown with walnut trees produces ~ 40% higher yields. 1 hectare of wheat/walnut mix yields the same as 1.4 hectares of each crop grown separately. This is an example of overyielding. Overyielding is when a polyculture (multiple crops grown together) produces higher yields than equal areas of the same crops grown separately. Other benefits of wheat and walnuts polycultures:

Trees provide shelter for the wheat from wind, rain, temperature swings etc.

Tree roots recover and utilize nutrients that leach beyond the wheat's root system.

Trees add organic matter to the soil with roots and leaf litter.

Tree growth is accelerated due to wider spacing, equal to ~80% more growth in the first 6 years.

These systems also offer a huge potential for carbon sequestration, improving water cycles, and conserving soils. There are 220 million hectares of wheat worldwide. Imagine the economic and ecological impact of incorporating trees at this scale.

How many times have you read a thesis based on a sum-of-the-parts where it ends with “So you basically get X part for free!”? Sometimes that’s true. But other times, all of the operating parts are intertwined, symbiotic, each directly influencing the value produced that is inappropriately solely attributed to others. A business may be undervalued, but you aren’t getting a single part for free. Sure, you can try to think of parts separately, but to actually split some of them would promise underyielding.

There comes an uneasy truth that, despite how comfortable we become with certain valuation approaches, there’s an endless nuance that guarantees disappointment if your goal is precision. For those who crave perfection, this can be painfully frustrating, but only until it’s realized that it is a major source of opportunity. Seizing it begins with building around a considerable margin of safety, not just to protect against the unknowns of the world, but to protect against our own limitations. Like traditional crops, investing requires endless work and unbridled patience. But this isn’t a science; investing is an art. The seasons are even less predictable, and cultivating strong ideas and harvesting full bounties requires an open mind and a willingness to look at things from different perspectives. Occasionally, we are provided gifts that wouldn’t otherwise be seen.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” and share the sum of its parts.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Lovely title Devin!

> How many times have you read a thesis based on a sum-of-the-parts where it ends with “So you basically get X part for free!”?

Yes! My favorite: “Buy AWS, Get Amazon Retail For Free.”