Bubble Trouble

“If you live among wolves, you have to act like a wolf.” - Nikita Khrushchev

Never mind the fact that a communist first spouted today’s opening quote. Across capitalism, there are few occurrences more fierce than the wolf-like battles fought to win in consumer product categories. Brand equity is powerful, but if not managed well, it can wither. In nascent categories, building it in the first place is a truly arduous task. Often, it becomes apparent that brands are merely renting market share rather than earning a special place in the consumer’s mind.

When considering leading brands of any one product category, the future is often imagined as a Coke vs. Pepsi-type scenario, with just a few dominant brands and the rest of the pack fighting for scraps. This type of framing is routinely applied to newer product categories, including nicotine pouches, where competition is intensifying. Considering historical precedent and the unique regulatory environment for nicotine products, this is not baseless. However, whether it’s nicotine pouches or otherwise, the evolution of another beverage category reminds us of the potential for turbulence. First-movers falling behind and unlikely upheavals are just two of the numerous instances in which expectations are dashed by the considerable uncertainty our world presents.

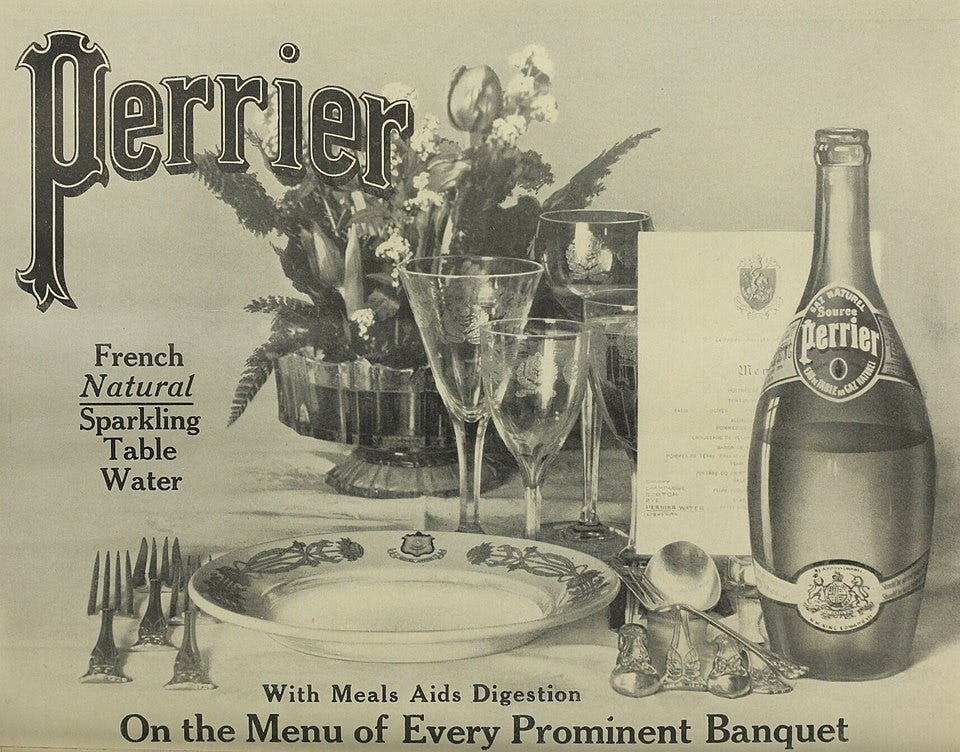

In the late nineteenth century, Perrier was created by drawing water from an ancient natural spring in Southern France. Finely carbonated and refreshing, the product was marketed as “the Champagne of mineral water,” appealing to those who were both sophisticated and well-off enough to afford something as extravagant as paying for water. Despite modest growth across France and the United Kingdom, the product’s positioning led it to remain more of an infrequent indulgence rather than a mainstream staple. That changed when the brand broke into the United States market in the 1970s.

Initially, the brand’s proposed efforts in the United States were met with criticism. Surely, Americans would reject such a pretentious product. Yet, with significant marketing, the company leaned into the product’s sophistication, alongside its foreign mystique. Messaging was refined. This wasn’t just an elegant product; it was a healthy product, with natural minerals providing what your body craves.

Product-market fit was proven in the decade and a half following 1975, when sales volumes increased by approximately a hundredfold. Perrier was undeniably a dominant force. But, as one would expect, the rapid growth did not go unseen by other beverage producers. Countless competing bottled water brands were introduced, the majority of which were uncarbonated but offered at far more attainable price points.

Despite competition remaining fervent, Perrier’s leading position was maintained and appeared to be solidified. However, a nationwide recall in 1990 significantly altered the category’s composition. In less than a year, Perrier’s market share more than halved to approximately 20%. The tainting of its crystal-clear image, paired against increasing brand investments from behemoths PepsiCo and Coca-Cola, promised Perrier would never fully recover. Presently, Perrier could be seen as a shadow of its former self, with an estimated market share of just under 10% in the United States and less than 4% globally. However, its success in shaping the bottled water category cannot go unappreciated, and with the sustained growth of the category, the product’s achievements have been nothing short of phenomenal.

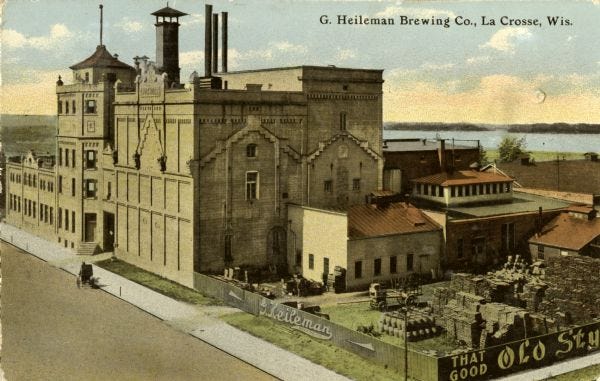

In 1980, LaCroix was launched in the United States by the G. Heileman Brewing Company.1 It wasn’t posh. It wasn’t pretentious. It was a carbonated water brand that could be enjoyed anytime, anywhere, and was affordable enough for everyone to acquire. Building out from the company’s roots in Wisconsin, LaCroix gained increasing popularity across the Midwest. In 1992 (the same year that Nestlé acquired Perrier), lacking a sophisticated understanding of the category, Heileman was unable to push the LaCroix brand further and sold it to a more capable owner, National Beverage Corp.

During the first two decades of LaCroix’s ownership under National Beverage, efforts to expand the brand nationally had proven difficult. Slowly but surely, distribution and shelf space were gained, making modest inroads across select states. Then, as if struck by a lightning bolt, LaCroix became supercharged. Sales volumes of soda had been steadily declining, and consumers were becoming increasingly conscious of sugar intake and the critical importance of hydration. Through organic marketing practices across social media, LaCroix targeted younger demographics, highlighting its zero-sugar content, appealing to health-conscious audiences. The message resonated, building tremendous affinity for the brand.

Increasing demand for the brand led LaCroix to strike deals with major grocery store chains, expanding its reach and improving shelf space. From 2010-2015, sales accelerated, with National Beverage’s 2015 10-K2 stating:

100% all natural LaCroix® Sparkling Water, our strategically largest and fastestgrowing brand, has set the pace in the Sparkling Water category that is rapidly becoming the alternative to traditional carbonated soda. With zero calories, zero sweeteners and zero sodium, the innocence of LaCroix has propelled it to the topselling all natural domestic sparkling water

For the next two years, sales remained robust, with similar language in the 2017 10-K describing the brand’s dominant position.3 In subsequent years, the language shifted from describing the brand as ‘dominant’ to ‘top-selling’, with an emphasis on new flavor combinations and variants receiving new packaging. The brand’s market share in 2017 was estimated to be 30% of the category, with significant growth expected to continue.

Unlike Perrier, LaCroix did not experience a sudden event that caused it to lose market share rapidly. Instead, it was the steady and unrelenting pressure of competition that ultimately slowed its growth. With limited regulatory hurdles and straightforward production requirements, the category was open to any and all beverage manufacturers, and many eagerly joined in. Shelf space was vied for, marketing expanded, and pricing became more aggressive. Pepsico launched its Bubly line in February 2018, and Coca-Cola launched AHA in March 2020. While National Beverage was well-off, these behemoths, relatively speaking, had infinite capital to fight, not to mention world-class distribution. In 2021, National Beverage’s 10-K highlighted development plans to expand LaCroix offerings, capitalizing on its already established brand loyalty.4 While still a major brand, the once extrapolated growth, assumed upon its once-dominant stature, fizzled. A chart of National Beverage’s stock price, below, captures the excitement during the 2015-2017 period.

Coca-Cola’s 2020 launch of AHA was met with clear expectations. The company had the experience, capital, and distribution, not to mention marketing muscle essentially on steroids, to make the brand a slam dunk. During the 17th Annual dbAccess Global Consumer Conference in June of that year, the brand’s initial momentum was highlighted:

Stephen Robert Powers, Deutsche Bank:

Is there any -- I mean, entering this year, we were at CAGNY, we were talking about, we were sampling AHA as a new launch this year, which unfortunately was timed against COVID, Coke Energy rolling out as a reformulated offering, and a lot of sizable regional offerings like the expansion of Costa into Hellenic markets. Some of those things, I’m assuming, have been either paused, or some of the investment has been pulled back as focus goes to the core. Have you -- are those initiatives paused? Or if we just think about them as reaccelerating as we get into the back half or even repeating as a launch in the following year? Or are any of those things now being just pulled back in or are off the table?

John Murphy, CFO, Coca-Cola

I think the short answer is sort of all of the above. But let me drill in. On AHA, AHA is doing very well in the U.S. given the context. It’s the top 15 growing trademark in retail dollars in the month of April, and it continues to demonstrate a lot of momentum as we go into the rest of the quarter.

By the same time the following year, AHA’s momentum had slowed significantly. The company discontinued some flavors while introducing others, with the discontinuations primarily attributed to the then-widespread shortage of aluminum cans. At 2021’s DbAccess Global Consumer Conference, Manuel Prieto, Coca-Cola’s Global Chief Marketing Officer, reiterated the brand’s potential:

So it is all developed only by the North America team for North America in mind. However, the new global category team structure very quickly identified it as a brand that has legs. And we believe that it can be scaled in many geographies, and we have quickly adopted it for Europe and China, where we’re launching as we speak.

Despite all the checkmarks indicating why AHA would succeed, it was ultimately an undifferentiated late entrant up against an endless array of lookalike brands. Within twenty-four months, Coca-Cola had wound down the majority of AHA’s distribution in the United States, opting to prioritize its premium Topo Chico brand, which it had acquired in 2017 for $220 million. Although AHA could be considered a failure, the refocus has thus far proven fruitful. During the company’s Q3’24 earnings call, Coca-Cola’s CEO, James Quincey, framed Topo Chico’s achievement (emphasis added in bold):

Topo Chico is another example. In the U.S., Topo Chico is the #1 premium sparkling water brand. We’ve driven strong consumer demand with a grassroots experiential campaign in 13 cities, featuring impactful displays connecting Topo Chico to food, music and art. In Mexico, we’re applying a similar playbook. We recently launched Topo Chico’s first-ever nationwide experiential activation with the Think Like An Artist campaign. This featured connections with local artists across 69 events in 5 cities and was amplified through social channels. During the quarter, Topo Chico Trademark grew volume nearly 20% globally. Year-to-date volume has increased tenfold compared to pre-acquisition levels in 2016.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

I own positions in Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. I own positions in tobacco companies such as Altria, Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Scandinavian Tobacco Group, and Imperial Brands. I also own positions in Haypp Group, a major online retailer of reduced-risk nicotine products.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

The G. Heileman Brewing Company was eventually acquired by Stroh’s, an overlap in the story of Schlitz Beer.