“It literally took the judges two minutes to see the winner, and then they concentrated on who is coming second.” - Dorian Yates

There are few bodybuilders more legendary than Dorian Yates. During his career, rather than strictly lifting progressively heavier weights, he focused on perfect form, quickly raising and slowly lowering each load. Instead of a fixed number of reps and sets, he would continue until his muscles only allowed him to partially complete reps, pushing until his muscles completely gave out. ‘Rep until failure.’ Yates recalls the strain leading to vomiting, being forced to crawl during recovery, and, at times, it even being difficult for him to raise his arms to accomplish basic tasks. It was ultimate determination. Sacrifice. Sacrifice that led him to retire after numerous injuries. But that sacrifice and his unconventional techniques also led him to greatness; six consecutive Mr Olympia wins from 1992 to 1997.

In any business, whether bodybuilding or otherwise, discipline is not enough to excel. Exceptionalism comes from having the right genes and frame, granting the ability to not only withstand immense stress, but to synthesize it into productive output. Many companies, even entire industries, lack the genetic makeup to become exceptional, leading to sustained operational underperformance and equally dismal investor returns. The tobacco industry, historically, has epitomized exceptional business. Persistent advancements in tobacco cultivation and the introduction of mechanized production resulted in higher product consistency and affordability. Capital was redeployed and diversified. Competition, industry consolidation, and deconsolidation ebbed and flowed. All throughout, immense profitability endured. But it wasn’t merely the genetic makeup and frame that led to sustained supernormal profitability. It was also from strain applied to the system.

Following tobacco’s introduction to Europe and its proliferation throughout the rest of the world, leaders—dictators, monarchs, parliaments, congresses, and all others—have continually attempted to minimize its influence. Actions centered on acute health risks during the second half of the 20th century. Limitations were applied to operators and consumers alike, impacting everything from production to who could purchase tobacco products and where use could occur. The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement applied even greater limitations in the United States. Anticipated to cripple the industry, it was instead akin to injecting a hefty dose of steroids. Restrictions to advertising, marketing, and promotion prevented new competition and allowed incumbents to slash their related budgets, causing profits to grow even larger for decades to come.

Those most critical of the idea that this continues will say that that was then and this is now—an environment with more looming regulations. However, the list of easiest-to-implement regulations with the clearest effects has largely been expended, leading various countries to attempt desperate actions. South Africa’s tobacco ban during Covid and India’s previous step-up in excise tax both fostered larger illicit markets, reducing visibility and denying governments much-needed funds. Pakistan is set to demonstrate similar. Now New Zealand is set to roll back several components of its generational smoking ban. All cases prove that the environment for legacy tobacco products is set to remain far more rigid than most believe. The base of industry profits marches higher, and legacy tobacco products require paltry reinvestment. While cash flows are bound to decline eventually, the rate will likely be slower and more gradual than pessimistic headlines have touted ad nauseam.

The greatest uncertainty facing the industry stems from the introduction of next-gen nicotine products. While equally contentious, and with countries taking markedly different approaches to regulating them, there is a likely future most easily identified by revisiting the principal reason any regulatory efforts are made at all. The tobacco usage prevalence cycle occurs in four stages, the first of which is an introductory period where prevalence is low due to limited disposable income. Historically, as countries become more wealthy, prevalence grows. However, rising wealth and prevalence lead societies to re-focus on health implications, ushering regulatory efforts to reduce usage. With most levers already pulled in developed nations, further increases in excise taxes are one of the only remaining tools—but as highlighted, the rate at which increases can occur is limited before unintended consequences occur. Therefore, the clearest and arguably most effective way to reduce tobacco-related harm is to embrace policies that encourage users switching from legacy tobacco to lower risk next-gen nicotine products. Such policies will also have profound impacts beyond benefits to societal health.

Most conversations about product affordability revolve solely around monetary costs. But the health costs of consuming nicotine via legacy tobacco products is far higher, and the majority of smokers quit because of current and future health costs, not monetary costs.1 What happens when health costs are largely eliminated? The latent human desire to consume nicotine that was previously suppressed would be unleashed. This, in essence, is the concept of re-nicotinization, which I highlighted in July 2022:

The New Era of Nicotine

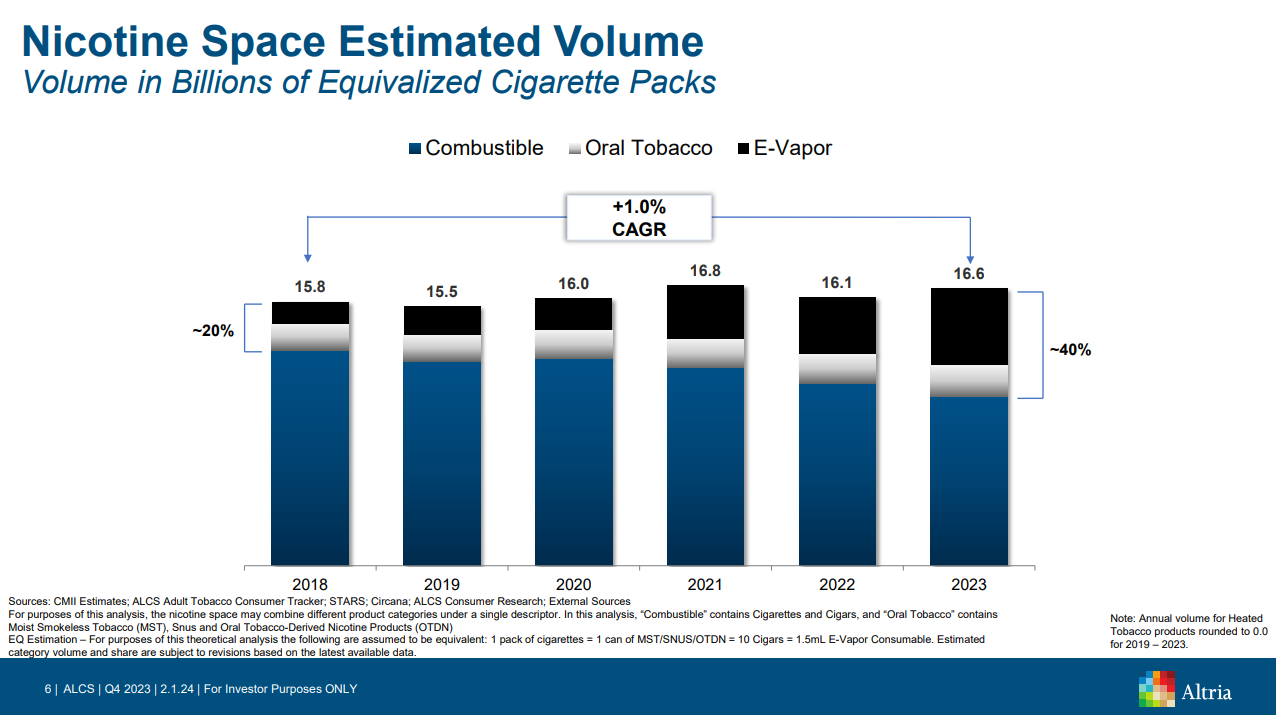

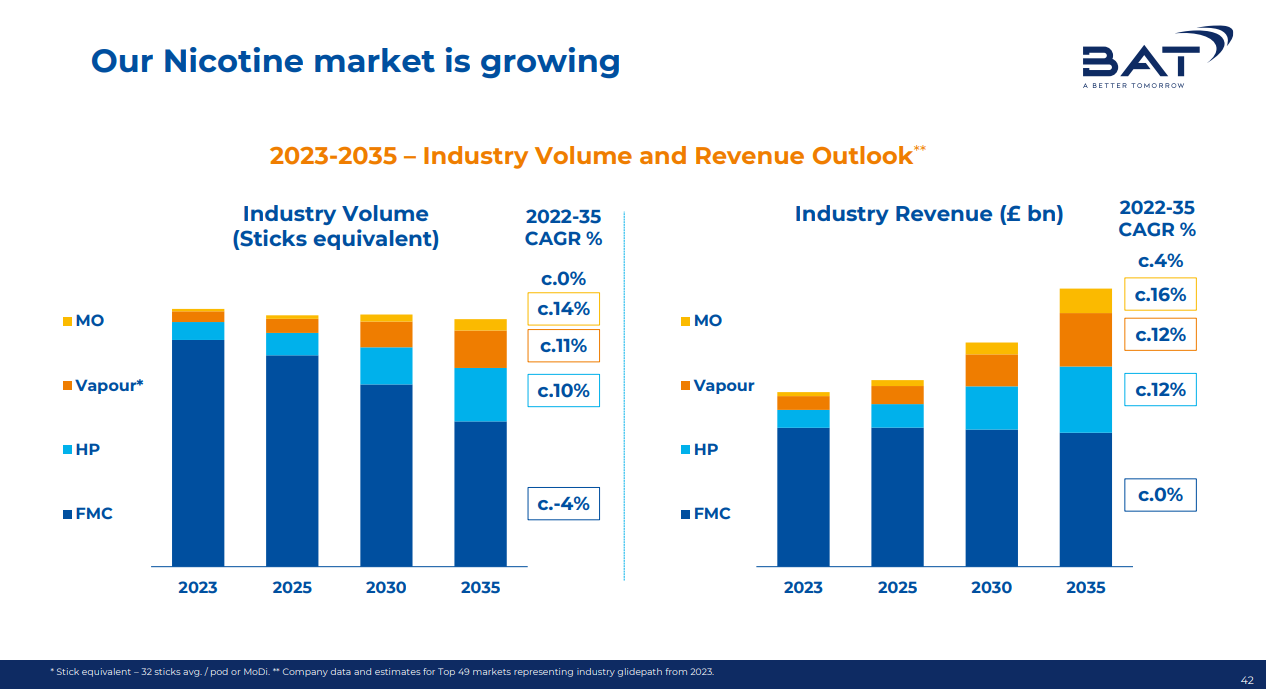

We are witnessing this unfold in real time, with major manufacturers highlighting that aggregate industry volumes aren’t exactly falling off a cliff:

Of course, volumes do not strictly equal value, and considerable uncertainty remains about how the growing value pool is divided amongst the value chain. New product categories have led to an increasing number of competitors, and illicit volumes continue to rise. Further, as more countries embrace regulatory frameworks centered on tobacco harm reduction, it stands to reason that existing regulatory barriers to entry may be lowered, leading to even more competition. Therefore, despite current industry stability, it remains likely that the equities of major manufacturers experience heightened volatility and greater multiple compression as the underlying companies navigate changing regulation, continue reinvestment into scaling new categories, and aim to foster brand loyalty for new products. However, shifting from looking years outward to decades, it is also highly likely that total nicotine consumption will be far higher than it is today, and while societies will benefit from the substantial reduction in tobacco-related harm, so too will the industry.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share. To further show your support, consider pledging a paid subscription to Invariant.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

I own positions in tobacco companies such as Altria, Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Scandinavian Tobacco Group, and Imperial Brands. I also own positions in Haypp Group, a major online retailer of reduced-risk nicotine products.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Very well done — I think the persistence and profitability of the tobacco industry despite (or perhaps because of) such heavy regulatory involvement bodes really well for an industry I’m very excited about: cannabis (both recreational and medicinal).

interesting, since i see fewer people smoking aroun me