Nicotine Certainty

“The life history of any industry is largely determined by two forces, the technical conditions of production and the character of the selling market. Every transformation in the organization of an industry can be traced ultimately to some change either in the methods of production or in the methods of marketing the product. It is in this light that we interpret and explain the development of our present capitalistic system, in the progress of which competition has been the driving force. Intensified competition has in each instance been the result of, or necessitated by, some technical improvement within the industry, or some alteration in the world market. That the tobacco industry is no exception to this general rule will become apparent as we attempt to explain its development in terms of these two factors, conditions of production and the selling market.” - Meyer Jacobstein, The Manufacture of Tobacco, The Tobacco Industry in the United States

Restrictions, heavy-handed rules, generational smoking bans, and now, even the proposed banning of cigarette filters. There has never been a shortage of silliness when it comes to the regulation of tobacco. Unfortunately, no matter the intentions, such silliness often results in unintended consequences; Cobra Effects.

Of the many cases, a prime example of Cobra Effects is Australian policy. Heavy restrictions on packaging and displays have been met with ever-increasing excise taxes, pushed to a rate well beyond reason. Tax at such a level has failed, weakening the government’s associated revenue, in addition to creating an extremely lucrative (and massive) black market.

The outcome in Australia should come as no surprise, given that it mirrors the same outcome that has played out elsewhere throughout time. Meyer Jacobstein, a member of the United States House of Representatives from New York from 1923 to 1929, authored The Tobacco Industry in the United States1, initially published in 1907, highlighting a strikingly similar development roughly two centuries prior:

Moreover, these Napoleonic wars burdened European governments, especially England and France, with heavy public debts. To wipe out these debts, import duties were greatly increased on all products partaking of the character of luxuries, including tobacco. The tobacco tax had always been considered a lucrative as well as a justifiable one. These increased duties raised the prices of tobacco to the consumer proportionately, thereby cutting down consumption, or at least checking its rate of increase. The falling off of our exports in the period subsequent to the Napoleonic wars was no doubt partly due to this factor. In England, for instance, the tax was raised in 1815 on imported tobacco, from twenty-eight cents per point to seventy-five cents per pound. This brought the duty up to nine hundred per cent ad valorem. England’s consumption consequently fell from twenty-two million to fifteen million pounds.

The English duties were so high that a special committee was appointed by Parliament to investigate the disturbed conditions of trade resulting from the increased tax. This committee reported that the prices of tobacco were so high that smuggling and adulteration of tobacco were made very profitable.

Every cycle begins and ends with a new cover of the same old tune. It is certain, irrespective of how ineffective, that special interest groups will continue to push anti-tobacco regulation. We are also witnessing such stances transform from being merely ‘anti-tobacco’ to ‘anti-nicotine’.

I am routinely asked why I invest in nicotine when such a perilous and unrelenting headwind exists. To simplify, aside from the industry’s remarkable consistency, profitability, and rewards for shareholders, there is a future certainty I believe to be far more powerful than the certainty of ever-stretching attempts of prohibition.

‘Certainty’ is somewhat of a taboo word. Using it suggests a degree of arrogance and a lack of appreciation for all of the uncertain variables that our world presents. Because of this, investors often use terms like ‘likely’ or ‘highly probable’ to describe conviction in how something plays out.

One notable investor who is bold enough to use the term ‘certainty’ is Greenlea Lane’s Josh Tarasoff. During a 2017 interview with the Ben Graham Centre, when asked how his investment strategy differs from most of the value investing community, Tarasoff began his answer (emphasis in bold):

I’d say there’re 3 ways. The first way is that in very common value investing culture, value investors tend to be comfortable with betting on consistency, and uncomfortable with betting on change. The classic Buffet thing is: are people going to buy this product 50 years from now? Is it durable? Are people still going to drink soda, and will Coca Cola have the biggest market share? Is Geico still going to have the lowest cost? And, to bet on change is more of the growthy temptation that if you do it, you’re undisciplined, imprudent and risky. What I believe is that, certain changes can be as certain and predictable as certain constancy. It just depends on the situation. For example, in my portfolio, I think more shopping being done online overtime is as certain as many constancies that I’d be willing to bet on, like consumer brands. I think that, traditional on-premise IT moving to the cloud is certain as one needs it to be. I think that more people having pet medical insurance is as certain as one needs it to be to prudently invest in it. There are certain patterns and frameworks that when there’s a way of doing something that’s both better and cheaper simultaneously, it will happen. Online retail is that, cloud computing is that, and probably electric vehicles are that. That’s one thing.

The other one is that when there’s a new way of doing something where if you do it that way instead of the old way, it’s a win-win for every party involved and no one loses, then that’s certain to happen too.

Concepts related to certainty are continually cited in Tarasoff’s work. In an essay about investing, Tarasoff writes:

Endgame

My investment theses are underpinned by what I call an endgame: a long-term state of affairs in which I have high conviction. The basis for this conviction is what I think of as overwhelming logic: forces that make too much sense not to prevail in the fullness of time.

An example: Years ago, I came to believe that because online retailing provides a superior customer experience at a lower cost structure than offline retailing, a majority of shopping should eventually move online. At the same time, because there are more advantages to scale and fewer reasons for market share fragmentation online than offline, the winners in online retail would eventually have significantly more sales than their offline counterparts in their heyday. Finally, because online retailers enjoy superior economic models, they should be worth greater multiples of sales than offline retailers. One online retailer stood out as having vastly stronger feedback loops than its competitors and as being exceptionally high quality. Greenlea Lane was able to invest because the valuation was such that the returns would be outstanding if the endgame were to play out as expected and decent even if it were not to.

The online retailer he is referencing? Amazon—one of his most successful investments. You might wonder how a high-flying mishmash of retail and technology, like Amazon, relates to an old, stodgy industry that manufactures and sells nicotine products. Surely, there aren’t many similarities.

My piece, Haypp Group: Skyward, stressed the point that nicotine pouches are, by far, the most affordable recreational nicotine product when measured on cost to one’s health. While not as low as nicotine pouches, nicotine vapor and heat-not-burn products also have lower risk profiles than legacy tobacco products, and radically so when compared to cigarettes. Currently, the prevalence of total nicotine usage faces a headwind because the largest group of current users are smokers, and, if you simplify, you can assume smoking shaves off years of a user’s life.

Part of my thesis for investing in a number of nicotine businesses is that nicotine usage prevalence will grow. I concluded in March 2024:

However, shifting from looking years outward to decades, it is also highly likely that total nicotine consumption will be far higher than it is today, and while societies will benefit from the substantial reduction in tobacco-related harm, so too will the industry.

I now believe that statement to be inaccurate.

Nicotine usage prevalence will grow, not just because products with lower health costs are appealing to more people who will become users, but because the average lifespan of those users will incrementally move towards that of non-users. It isn’t just highly likely. It is inevitable.

Certainty about nicotine’s ‘endgame’ does not, in isolation, make for a compelling investment case, especially considering that despite higher usage prevalence, more usage may be pushed toward the black market. However, the endgame contrasts sharply with the prevailing narrative that the nicotine industry faces an unavoidable extinction. Widely, next-gen nicotine products are viewed as a clever (if not desperate) attempt to merely slow the industry’s decline, rather than significantly enhance its long-term trajectory (never mind the fact that the industry has always been a growth industry if measured on profits rather than volumes). Of all the five and ten-year DCFs models you may come across, I very much doubt even one captures the potential value of the endgame.

At the same time, there appears to be a growing sense of certainty that specific product categories will win out, driving the majority of growth. If the future is to rhyme with the past, as it often does, we should be careful when making such assumptions. When the endgame is reached, all current product categories may very well still make up significant shares of the collective market, but new forms of nicotine delivery, not yet seen, may be introduced into the mix.

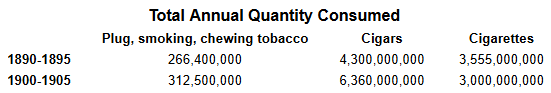

Pointing back to Jacobstein’s book, the data it is concerned with makes no mention of heated tobacco, vapor, or modern oral. Why would it when those products were nearly a century away? In that same vein, it would have been all too easy when reading his book in the year it was published, 1907, to make assumptions of category trajectories based on collected data.

These figures, in hindsight, are surprising. While cigarettes declined in volume, cigars radically increased, making up the majority of the market. This evolution is somewhat counterintuitive, as cigars were the most expensive form of tobacco. This data, more than anything, reflects the rapid rise in the average American’s wealth, and by extension, purchasing power, expressed as higher consumption, but an interest in higher quality products. Naturally, escaping these figures is the vast innovation that would occur in tobacco cultivation, refinement in curing, advances in manufacturing, and growing efforts within marketing.

If you enjoyed this piece, hit “♡ like” on the site and give it a share.

Questions or thoughts to add? Comment on the site or message me on Twitter.

Ownership Disclaimer

I own positions in tobacco companies such as Altria, Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco, Scandinavian Tobacco Group, and Imperial Brands. I also own positions in Haypp Group, a major online retailer of reduced-risk nicotine products.

Disclaimer

This publication’s content is for entertainment and educational purposes only. I am not a licensed investment professional. Nothing produced under the Invariant brand should be thought of as investment advice. Do your own research. All content is subject to interpretation.

Jacobstein, Meyer. The Tobacco Industry in the United States. The Columbia University Press, 1907.

I don't smoke but have long been anti-anti-nicotine. The no fun police are humorless scolds. I suspect they like drawing attention to their own purported virtues by highlighting the "sins" of others without any commensurate health benefits. Americans started to get really really fat right around the time we weaned ourselves off most nicotine. Smoking isn't great, but gums and lozenges are probably fine. There are worse things (including obesity). And it is okay if other people get a little pleasure out of life in their own preferred way.

I agree with the conclusion on total nicotine consumption volume increasing. I think where the thesis could break as a nicotine investor is that regulators become overzealous and consumption shifts towards illicit unregulated products. The other key risk to watch out for is regulatory barriers for NGPs are lax enough that you have tons of entrants flooding the space and pushing prices down. Essentially, we need regulators to take an intermediary stance that preserves the moats of incumbents but is not overly stringent so as to kill the market altogether.

I think regulators are incentivized to achieve this outcome given the potential tax revenues, but there’s not guarantee they won’t take irrational measures to curb nicotine consumption.